Deeds that cry out to heaven also cry out for hell

In the city that is home to Harvard, MIT, Tufts, Boston College, Northeastern, U Mass—some of the world’s greatest Universities—the broken bones, broken lives we’ve seen play out in Boston this week rile up something deep within—something that challenges sophisticated, academic ideas of relative truth and tolerance: the longing for justice.

In the city that is home to Harvard, MIT, Tufts, Boston College, Northeastern, U Mass—some of the world’s greatest Universities—the broken bones, broken lives we’ve seen play out in Boston this week rile up something deep within—something that challenges sophisticated, academic ideas of relative truth and tolerance: the longing for justice.

We want what is wrong to be put right. For the world to be put right. We want murderers to suffer consequences for the lives they’ve snuffed out, the crushing physical pain they’ve inflicted, the wrenching emotional pain of living with loss—of limbs, of abilities to think and run, most of all, loss of the face and presence of those most dear.

President Obama said, “The families of those killed so senselessly [and the wounded] deserve answers.” Answers, but curiously no mention of justice or punishment for the ones who killed and maimed. In today’s culture we tend to value mercy and compassion almost to the exclusion of justice. Yet events like the Boston Marathon bombing compel us to put the issue of justice squarely on the table.

We don’t hear too many voices calling for tolerance and understanding of the private realities of two young men who load pressure cookers with gunpowder, ball bearings and nails and stand back and watch their handiwork slaughter innocents and destroy property. We don’t hear the professors who teach that there is no absolute standard of good or evil cautioning their fellow Bostonians that we must not judge.

We mourn. We weep with those who weep. And we long for justice–“being in conformity with what is righteous and good.” If we have no confidence that absolute good exists, then how do we find grounds to determine that an act is absolutely wrong and deserves punishment? Are these professors condemning these acts of terrorism? Or, if all values are personal and subjective, are they limited by their worldview to saying that they prefer that young men not do these sorts of things? It would be interesting to listen in on classroom discussions this week.

For those who intuitively sense the absolute wrongness of the bombings, what might justice look like? Tamarlan Tsarnaev died in a gunfight with the police. Is that justice? His one life is lost, but he killed four and injured over one hundred and seventy. The pain of the families who lost loved ones and the pain of those who suffered terrible injuries will go on and on across the lifetimes of so many. Tamarlan’s flight and gunfight with authorities lasted minutes. Does such short endurance of fear and pain amount to justice?

Police shot Tamarlan’s brother, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, captured him and took him to a hospital for treatment. Suppose he recovers and spends the rest of his life in jail…is the humiliation of a trial and a lifetime of being locked up just? Are the consequences of a lifetime in jail more painful to endure than the consequence of death? What if he tells the police and the victims he is sorry for resorting to such violence…should he be forgiven? Should he be set free?

Most statues of Lady Justice show her with a scales in her hand. We have an innate sense of symmetry that compels us to think that the punishment should fit the crime. The perpetrator should experience more pain, not less, than his victims did. What degree of punishment fits such a massive crime?

Boston College professor Peter Berger, a devout Catholic, has written, “Deeds that cry out to heaven cry out for hell.”

In a culture where being judgmental is often viewed with far greater contempt than what is being judged, the idea of hell has become an embarrassment. Except at times like this. In the face of such evil condemnation seems insufficient. Damnation seems more just.

Jesus was not embarrassed about hell. “Fear him who can destroy both body and soul in hell,” he said. He would rather we all fear God and hell than ignorantly and fearlessly exit this life expecting either extinction or some vague idea of awe.

If hell is not real then there doesn’t seem to be real justice for someone like Tamerlan Tsarnaev. Our choices are not imbued with eternal significance.

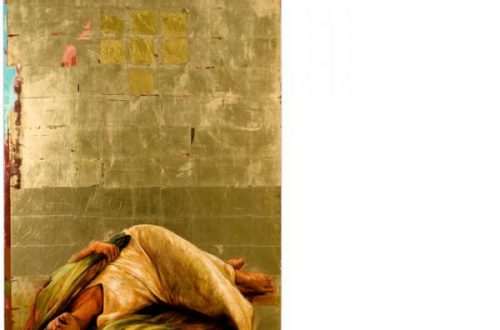

Further, if Jesus didn’t take our hell upon himself then his sacrifice was merely physical and emotional. And there were thousands of others who suffered the same fate at the hands of the Romans. Who lingered much longer in agony on a cross.

But if hell is real, if Jesus was made sin and separated from the Father, then he suffered the pain of crucifixion and hell together—pain beyond imagining. If we ignore this, if we choose our own way without regard for or thankfulness to the one who created us and died for us, our cosmic treason cries out for a great punishment. Without the cross we all face justice.

But when we believe in the Lord Jesus the Father forgives us, not because he merely shrugs off our hateful anger or jealousy or pride or even murder, but because his Son has already suffered our punishment for us. At the cross we, even Dzhokhar, can find mercy. And love beyond imagining.

“But he was wounded for our transgressions; he was crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace, and with his stripes we are healed.” Isaiah 53:5