On what basis do we approach God and experience His forgiveness?

Scripture teaches that God created people to exist in a deeply personal and enrichening relationship with Him. Indeed, it’s the basis for genuine human flourishing in all areas of life.

Scripture also teaches that the entrance of sin into the human race caused an immediate and permanent estrangement between people and their Creator-King. To put a fine point on it, in their fallen human state, everyone is alienated from the Lord, as well as from each other.

On what basis, then, can people approach God and experience His forgiveness? Jesus’ parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector, which is recorded in Luke 18:9–14, provides two diametrically opposite responses to the preceding question, along with two dramatically different outcomes.

Jesus especially had in mind religious legalists who were convinced of their own “righteousness,” while at the same time treating other people with contempt. Metaphorically speaking, those who were self-assured regarded everyone else as being despicable.

The Greek adjective translated “righteousness” comes from a root term that means “straightness” and refers to that which is in accordance with established moral norms. In a legal sense, righteousness means to be vindicated or treated as just.

Jesus described a scene in which two men made their way up to the Jerusalem temple (which sat on a hill) to pray. Yet, each person came from entirely different backgrounds.

On one end of the spectrum were the Pharisees. They were renowned for their observance of the laws of tithing, fasting, and ritual purity. Also, by reputation, Pharisees were legalistic and fanatically devoted to their religious traditions.

On the other end of the spectrum were the tax collectors. They served as agents of the despised Roman government. They were also considered ceremonially impure, for they had frequent contact with Gentiles.

It’s easy to see why the Pharisee in Jesus’ parable showed disdain for the tax collector in the temple precincts. An imagined scenario involves the religious leader entering the shrine complex. As he does so, he glares with disgust at the tax collector, whom he considers to be morally repugnant.

The Greek phrase rendered “about himself” (v. 11) indicates that the Pharisee was his own ethical point of reference and that his statements were made out loud. This ensured that others (including the tax collector) would take note as the religious leader celebrated his sterling lifestyle.

In essence, the Pharisee was not praying sincerely. Rather, he was putting on a show in order to gain the applause of people.

Evidently, the religious leader positioned himself in a prominent place (such as the inner court of the temple) to make his declarations. Also, being filled with self-confidence and arrogance, he wasted no time in announcing to God how great he was, especially in contrast to the dishonest tax collector. Today, these two individuals might be comparable to a renowned bishop within a denomination versus a notorious drug dealer in the community.

In contrast to the haughty Pharisee, the tax collector stood some distance away (perhaps in the Court of the Gentiles, the outermost section of the temple). In fact, he did not even dare lift his eyes to heaven as he prayed. It was if the tax collector remained outside in the church parking lot, while the Pharisee stood within the middle of the sanctuary so that all the attendees could see and hear him trumpet his piety.

The tax collector was filled with abject sorrow for his sin, and he repeatedly beat his chest over his spiritual bankruptcy and ethical failures. The only thing he could think of doing was to plead with God for “mercy” (v. 13), even though the tax collector knew he was a “sinner.”

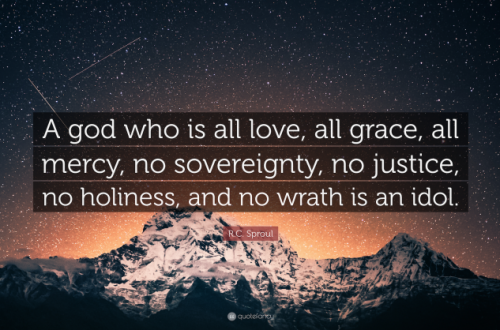

The Greek verb rendered “have mercy” literally means “to be propitiated.” The implication is that the tax collector was asking the Creator to turn away His wrath from the penitent’s seemingly innumerable transgressions.

The Father, in love, could do this because of the atoning sacrifice that His Son would make on the cross. Because Jesus is the offering for our iniquities, God’s wrath is appeased and the punishment for our trespasses has been satisfied (see Rom 3:24–26; 1 John 2:2).

Jesus’ statement in Luke 18:14 draws attention to an intense irony. Specifically, when the two men went home, it was the tax collector, not the Pharisee, whom God “justified” (v. 14). The Greek verb translated “justified” signified a court setting, with a judge announcing an individual to be “not guilty.”

As noted earlier, Jesus’ parable highlights two different ways of relating to God. The Pharisee’s prayer was uttered in an attitude of immense hubris. As if to impress God, the religious leader noted a list of vices that he abstained from and another list of devout practices in which he engaged.

It’s noteworthy that these pious observances went well beyond even that which was prescribed by the Mosaic Law. What the Pharisee boasted about himself might have been completely true, but the attitude of his prayer was completely wrong.

The tax collector’s prayer was uttered under great convictionof sin. Even as he implored God for mercy (to turn away His wrath), the tax collector recognized who and what he was, namely, a sinner (someone who had broken God’s law countless times).

The point of application is that humility and repentance, not arrogance and self-righteousness, please God. The latter pair causes a person to despise others and prevents him or her from coming to God.

There is no risk in admitting our sins to the Creator, for He already knows about them. And when we come to Him in repentance and faith, He responds by welcoming us into His sacred presence. This, then, is the only basis for approaching God and experiencing His forgiveness.

Jesus’ parable also teaches that in the Lord’s kingdom, there is no fighting for first place. After all, Jesus already has that position. Moreover, there is no pushing among the arrogant for a more privileged position. There is only one position for Jesus’ followers—the position of a humble, repentant bondservant.