The Tower of Babel

Genesis 11:1–9

Time: The dawn of human history

Place: The Fertile Crescent

Lesson Aim: To note that God will not permit the rebellious acts of the proud to succeed.

Introduction

Noah’s descendants at a plain (or valley) in Shinar were so filled with pride that they had the audacity to defy God’s will. We can only imagine the conflict that arose after God confused their language. There must have been huge misunderstandings, arguments, and estrangements.

When we arrogantly focus on ourselves and what makes us happy, we end up in conflict with other people who are doing exactly the same thing. Everybody can’t get his or her own way at the same time.

I. Humanity’s Arrogance: Genesis 11:1–4

A. A Common Language: v. 1

In the previous lessons we studied this quarter, we learned that the ripple effects of human disobedience brought alienation between brothers and sisters, within families, and among entire communities. Finally, the rebellion against the Lord’s plans began to infect the entire population. Those are the sad facts we must face in Scripture.

Genesis describes what God tried to do about the shattered relationships between humanity and Himself and among humans themselves. Indeed, the situation was so hopeless that only God could bring about a change.

The human race had sunk to such depths of depravity that God had to intervene. Human corruption and violence could not be tolerated indefinitely. The account of the Flood emphasizes that God is to be taken seriously, not trifled with or ignored.

Once the cataclysmic ordeal was over, the occupants of the ark left the vessel and returned to dry land. Genesis 9:18 specifically mentions Noah’s three sons, Shem, Ham, and Japheth. The so-called Table of Nations provides additional information about these individuals and their descendants. Japheth’s descendants are listed in 10:2–5; Ham’s descendants are listed in verses 6–20; and Shem’s descendants appear in verses 21–31.

The only person who receives extended comment is Nimrod, a hunter and empire builder (vv. 8–11). Also, verses 1 and 32 state that after the Flood, the clans that descended from Noah’s sons dispersed “over the earth” and repopulated the land. There is also some sketchy information about the locations of these clans and the languages they spoke. Chapter 11 provides the historical context for this scattering of humanity.

Like his sons, Noah also left the ark. He is referred to as a “man of the soil” (9:20), which means he was a farmer. “Soil” renders a Hebrew noun that is translated “ground” in 2:7 and 5:29, linking Noah with Adam.

God created Adam from the “dust of the ground” (2:7). Also, the “ground” was “cursed” due to Adam’s transgression. In 5:29, Lamech, the father of Noah, voiced the hope that through Noah the Lord somehow would provide relief from the curse.

Perhaps in keeping with the above sentiment, after the Flood, Noah made a fresh start by planting a vineyard (9:20). But then, he drank so much wine that he became overheated. Next, while laying in a drunken stupor in his tent, he “uncovered” (v. 21) himself to cool off.

One of Noah’s sons, Ham, saw his father undressed. He not only violated Noah’s dignity, but also reported the circumstance to his brothers (v. 22).

Out of modesty and respect for their father, Shem and Japheth took a cloak, draped it across their shoulders, and walked backward into Noah’s tent. They did this to avoid directly seeing their father undressed (v. 23).

When Noah finally awoke from his hangover and was told what Ham had done (v. 24), Noah was so outraged that he prophetically pronounced a curse on Canaan, Ham’s future descendants (v. 25). Noah declared that they would be enslaved by the same sinful disposition that had subjugated Ham. Moreover, the Canaanites would become the most menial of servants to the descendants of Ham’s brothers.

Next, Noah pronounced a blessing on Shem and Japheth. Noah reiterated that the Canaanites would become subject to the descendants of Shem and Japheth (vv. 26–27). After the Flood, Noah lived a total of 350 years and died at the age of 950 (vv. 28–29).

Once the Flood was over, God promised never again to destroy all life with a catastrophic deluge of water (8:21–22; 9:11, 15). This promise, though, did not mean the Creator would forego ever again intervening to deal with human sin.

The episode involving the tower of Babel recorded in chapter 11 shows us a unique example of divine judgment on widespread evil. Specifically, the Lord confused human language and scattered the human race across the face of the planet. Before this episode, as verse 1 notes, everyone spoke a common “language” and vocabulary.

Furthermore, it would not be until the day of Pentecost thousands of years later that God began to reverse the confusion that occurred at the tower of Babel. Whereas then God scattered the human race over all the earth, on the day of Pentecost, He brought all sorts of different people back together to hear the message of salvation proclaimed by Peter and the rest of the apostles (Acts 2:4–11).

B. A Movement of People Eastward: v. 2

With the passage of time, the descendants of Noah grew in number. This was a fulfillment of God’s pronouncement of blessing on Noah and his family, in which the Creator directed humanity to “be fruitful and increase in number” (Gen. 9:1; see 1:28).

Verses 1–9 of chapter 11 focus on one group of people who settled in a “plain in Shinar” (v. 2). In ancient Near Eastern texts, Shinar was referred to as Sumer, an area in Mesopotamia that is now part of modern-day, southern Iraq. The region was known for its rich alluvial soil, abundant wildlife, and mineral deposits found in the neighboring mountains.

The Tigris and Euphrates rivers were the most prominent physical features in the region. Throughout the following centuries, inhabitants would create a vast network of irrigation canals to support a diverse agricultural system. In turn, the water supplied by these two rivers was a determining factor in the religious, economic, and social life of Mesopotamia’s residents and kingdoms (including Assyria and Babylonia).

C. A Decision to Make a Great City and Lofty Tower: vv. 3–4

In the plain of Shinar, the survivors of the Flood had the opportunity to rule over God’s creation as His faithful vice-regents. Tragically, the human race decided to rebel against this mandate (Gen. 1:26, 28; 9:1–2) and operate in a sinful, arrogant manner.

In particular, 11:3 reveals that the inhabitants sought to bring a halt to their expansion across the face of the earth. Instead of voluntarily scattering about the region and beyond, they choose to congregate in one place and build a city to match their grand ambitions. Generally speaking, there was nothing inherently wrong with creating a city, except that in this case, the people at Shinar were deliberately disobeying God’s command to repopulate the land.

For building materials, the residents decided to use sunbaked or kiln-baked bricks, with “tar for mortar” (11:3). The biblical text contains a hint of sarcasm when it notes that the inhabitants expected to carry out their ambitious building scheme without even being able to obtain stones and true mortar.

Presumably, these individuals had to resort to using crude materials (which most likely consisted of a claylike mixture of mud and straw) because they did not have immediate access to anything better. Another possibility is that it would have been too time-consuming and costly for them to journey to the mountains to quarry and haul back to their construction site stones weighing many tons.

According to verse 4, these survivors of the Flood wanted to “make a name” for themselves. This suggests the sinful desire to obtain increased fame and enduring significance (contrast with 12:2).

The builders of Babel expressed their evil intention in pride. Specifically, they decided to adorn their city with a colossal tower that would impress others.

The structure would also give the inhabitants ample reason to remain where they were and avoid the risk of being “scattered” (11:4) all over the world. Furthermore, the description of the planned skyscraper as one that “reaches to the heavens” probably indicates a belief that the result of the construction efforts could make Shinar’s residents equal with God.

Archaeologists tell us that the builders of other towers in Mesopotamia had similar pretensions. The ziggurats they constructed were square at the base and pyramid-like in shape. At the apex of such a massive, lofty, and solid-brick edifice was a small shrine that supposedly served as the gateway between heaven and earth (28:12, 17).

Sometimes the shrine was covered with blue enamel so that it would more easily blend in with the sky, the reputed celestial home of the gods. For instance, the ziggurat of the god, Marduk, built later at Babylon was called Etemenanki, which means “temple of the foundation of heaven and earth.” Also, the ziggurat at Larsa was called Eduranki, which means “temple that links heaven and earth.” Moreover, the ziggurat at Sippar was called Simmiltu and means “temple of the stairway to pure heaven.”

What a contrast this sort of heaven-defying pride is to the biblical plan of salvation. In the person of the Lord Jesus, God came down to a helpless humanity. The Savior desires that we humbly acknowledge the futility of our own efforts and rest solely on His sacrificial work on our behalf.

After all, as James 4:6 declares (quoting Prov. 3:34), God opposes the proud, but lifts up the humble. Theoriginalrecipientsofthe epistleapparentlyhadproblemswithbackbitingandjudgmentalattitudes.Tochallengethesesins,thewriterissuedaseriesofcommandsin4:7–10.

TheexhortationsweregiveninaGreektensethatsignifiedtheurgentneedtomakeadefinitebreakfromarrogantsinfulpractices,whichcouldquicklydestroyunityinthebodyofChrist.Theauthor’saimwastorestoreharmonyamonghisfellowbelieversandtopromotepersonalholiness.

Tothatend,Jamescalleduponhis readerstorejecttheirpridefulconductandtodrawneartoGodwithrepentanthearts.Inturn,thiswouldpromoteaharmoniousrelationshipwithGodandone’sfellowbelievers,bothofwhichareessentialforgrowthanddevelopmenttowardspiritualmaturity.

Aswegrowstrongandmatureinthefaith,wewillnotwaitforotherstotaketheinitiativeincreatingharmony.BecausewehaveknowntheLordfora while,wehavethecouragetotactfullyexposerelationalproblemssotheycanbeaddressedinaconstructivemanner.

II. God’s Assessment: Genesis 11:5–9

A. The Divine Investigation: vv. 5–7

In ancient times, Mesopotamian idol worshipers built mountain shrines with one or more descending stairways or ramps so their pagan deities could come down, receive veneration, and bless the worshipers. Contrast this with the situation involving the people at Shinar.

When God manifested His holy presence (described in human terms as the “Lord” coming “down to see the city”; Gen. 11:5), it was not to bless humankind, but to investigate their activities and judge them. Of course, the all-knowing Creator was fully aware of the progress the builders were making and the selfish, egotistical motives behind their efforts.

Previously, in the ancient Eden orchard, the Creator thoroughly examined the situation involving Adam and Eve before rendering His judicial sentence on them (3:8–19). Likewise, God, as the righteous Judge, scrutinized the circumstance involving Cain’s slaying of Abel before consigning the murderer to be a wandering fugitive (4:10–12). Later, during the lifetime of Abraham, the Lord dispatched His angels to check out the wicked acts being committed in Sodom and Gomorrah before punishing the city’s inhabitants (18:20–21).

In the episode recounted in chapter 11, all the inhabitants of Shinar spoke a common “language” (v. 6), for they traced their family lineage back to Noah. God recognized that their unhindered ability to communicate was a chief reason the people were able to cooperate in an evil plan.

Moreover, if the agitators continued to scheme with one another, they might cooperate in yet more wicked projects. Conceivably, nothing they proposed to do would be beyond their ability to achieve.

To prevent the preceding tragic outcome from happening, the Lord decided to “confuse” (v. 7) the people by causing them to speak different languages. Bringing this about would prevent them from being able to “understand” one another’s speech.

The above outcome was appropriate. After all, the people sought to build a lofty tower that was high enough to extend to the heavens (v. 4). So, in response, the Lord is depicted as coming down to thwart their self-centered, godless rebellion.

Verse 7 portrays the Creator-King decreeing, “Let us go down.” There are various explanations for the use of the plural here. Some consider this to be a hint of the Trinity, namely, a plurality within the divine unity of the Father, Son, and Spirit. Another possibility is that the Hebrew signifies either a plural of majesty (for example, the royal “we”) or a situation in which God addresses the statement to Himself.

A third group proposes that God and His heavenly angelic court are in view (Gen. 1:26; Isa. 6:8). In this case, while the cosmic attendants are included in the statement, it is God who passes and executes judgment.

It remains not clear, however, in what sense the members of the angelic court participated in God’s judicial sentencing. One option is that the assembly of heavenly beings governed the world and communicated with humanity under God’s royal authority.

B. The Divine Disruption: vv. 8–9

God, as the sovereign Lord of the cosmos, prevented the completion of the building project by scattering the people at Shinar (Gen. 11:8). Scripture does not give the details concerning how this came about.

Presumably, the inability of Noah’s descendants to communicate effectively with one another brought about intensified frustration and failure. In turn, the preceding circumstance resulted in the spread of individuals across the face of the entire planet. This outcome mirrors the banishment of Adam and Eve from the Eden orchard (3:23) and the expulsion of Cain from his native land (4:12).

In the ancient literature of Assyria and Babylon, the proper name, Babili, meant “gate of the god(s).” It corresponds to the Hebrew noun transliterated as “Babel” (11:9) and is similar in sound to the verb rendered “confused” (which is bālăl' in Hebrew).

Here we find a play on words in which the biblical text deliberately substituted one meaning for another to make a theological point. Specifically, despite the vaunted claims and evil ambitions of Noah’s descendants, they would fail in their efforts to construct a gateway to God.

Instead, the Lord would undermine humanity’s grandiose plans by causing different groups of people to no longer understand each other’s speech. Suddenly, each group now had its distinctive language. Obviously, this verbal isolation contributed to social isolation and resulted in the scattering of earth’s inhabitants.

Scholars think that Babel, the location of the infamous tower, was at or near the site of the later city of Babylon. After all, Babel sounds like Babylon. Furthermore, Babel was built in “Shinar” (v. 2), or Babylonia, the region that had Babylon as its capital. Later in history, Babylon became a symbol of evil to Jewish and Christian writers, probably because of the tower and because of the exile of Jews in Babylon in 586 B.C. (2 Kings 25; 2 Chron. 36; Jer. 39).

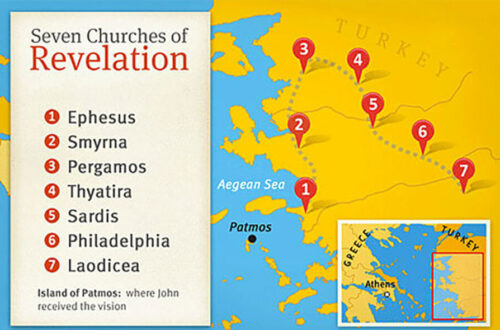

The Apocalypse says concerning this city, which once planned a tower that would dominate the sky, that its “sins are piled up to heaven” (Rev. 18:5). In contrast to Babylon is the “Holy City, the new Jerusalem” (21:2), that will one day come “down out of heaven from God.” Whereas Babylon was a cesspool of all sorts of wickedness, the new Jerusalem would surpass the beauty of everything else God had ever made.

As was noted earlier, the account of Pentecost recorded in Acts 2 provides a stark counterpoint to the episode about the tower of Babel appearing in Genesis 11. On the day of Pentecost, the Lord overcame the divisions of speech by enabling believers to speak in many different languages (Acts 2:5–11).

This episode represented the way the gospel can speak to people in every one of the world’s language groups. In baptismal union with the Son, the Father does not separate people to dilute their evil, but rather unites believers in righteousness.

Chiastic (Inverted Parallel) Structure of Genesis 11

AThe whole earth had one language (v. 1)

B Settled in Shinar (v. 2)

C Come, let’s make bricks (v. 3)

D Let's build for ourselves (v. 4)

E a city and a tower

F And the Lord came down to see

E' the city and the tower (v. 5)

D' that the humans built (v. 5)

C' Come, let’s confuse (v. 7)

B' Scatteredfrom Shinar (v. 8)

A'Confused the language of the whole earth (v. 9)

Key takeaways

Genesis 11 recounts the efforts of Noah’s descendants in a plain at Shinar to build a tower that would reach to the heavens (v. 4). In turn, God thwarted their arrogant and evil plans by confusing their language (v. 7). As believers, we may not be as bold and prideful as them, but at times we find ourselves opposing God’s will. If we persist, the result can only be misery for us.

1. WORLDLY AMBITION. The episode involving the tower of Babel reminds us that our cravings for success and fame easily take the place in our hearts and minds that belongs only to God. When we are consumed by worldly ambition, we find ourselves at odds with God and His will for our lives.

2. SPIRITUAL ADULTERY. Devotion to our illicit desires is a sinful attitude and therefore is friendship with the world (James 4:4). God will not accept a rival for the devotion of His covenant people. He expects undivided loyalty and provides His grace to enable us to shun all forms of spiritual harlotry and remain true to Him.

3. ARROGANT CONFIDENCE. We live in a culture obsessed with planning and goal setting. “If you can visualize it, you can achieve it,” is a mantra of our age. From Genesis 11 we see that all planning and goal setting must remain tentative (James 4:13–17). It should also be contingent on God’s will. Only His will is deserving of the trust and confidence our culture teaches us to arrogantly place in our plans and goals.

4. SELF-ABASEMENT. Humility involves choosing God over worldly enticements and then deciding to be loyal to Him. Christlike humility realizes that intimacy with God demands moral purity and is willing to repent to experience it. Just as Jesus promised (Matt. 23:12), self-abasement leads to exaltation by God.