A Historical Review: Black Women Who Won the Battle to Preach

Any review of women’s religious history is incomplete “without an adequate grasp of the groundbreaking work” of Black preaching women.[1] Historian Bettye Collier-Thomas in her book Daughters of Thunder: Black Women Preachers and Their Sermons, 1950–1979, explains that during the nineteenth century and the twentieth century, “in most black religious traditions, women won the battle to preach.”[2]

The Call of Women to Preach

Centuries prior, Quaker Margaret Fell Fox wrote about the call of women to preach in her 1666 pamphlet, Womens Speaking Justified. She presented arguments supporting this call beginning with the spiritual equality of humanity. Fox declared that “women’s speaking” was “justified, proved and allowed of by the Scriptures,” because “women were the first that preached the tidings of the Resurrection of Jesus, and were sent by Christ’s own command” (John 20:17).[3]

A Historical Review of the Preaching Ministry of Black Women

Turning to the nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries, during this time period women pursued God’s call to ministry in a variety of ways. And, both leaders and evangelical organizations supported them. Previously, I wrote about the ‘Bible Women’ in China, women who largely founded the Christian church in China through evangelism, teaching, and preaching. In this article, let’s review the history of Black women’s public preaching ministry.

Exhorters: Itinerant Ministers and Evangelists

Many of the early Black preaching women began their ministry as an “exhorter.” Exhorters were licensed by the church and spoke to assembled groups of people by giving a testimony, praying, and advocating for sinners to repent of their sins.[4] Some exhorters substituted for itinerant ministers, while others became evangelists.[5] In the twentieth century, Collier-Thomas writes that Black churchwomen “became more outspoken and began pressing for the right to preach and for equality in the polity.” As a result of their efforts, “The number of women licensed and ordained to preach grew.”[6]

Elizabeth

The earliest American Black female preacher, known only as Elizabeth, preached across the United States for almost fifty years. She embraced faith at twelve years of age while a slave in Maryland. Freed at age thirty, she was forty-two when she felt the Holy Spirit confirming her call to travel and preach. She held her first prayer meeting in 1808, and continued to teach and preach, though at times she risked being re-enslaved.[7]

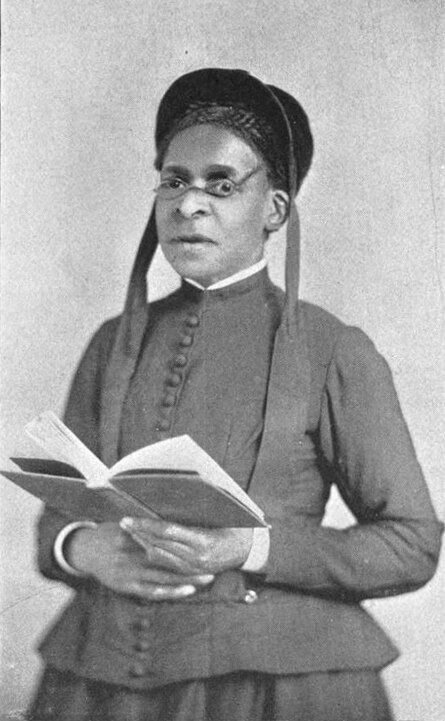

Jarena Lee

Jarena Lee (1783–1849) describes in her 1836 autobiography, The Life and Religious Experience of Jarena Lee, A Coloured Lady, Giving an Account of Her Call to Preach the Gospel, how she initially balked even though she felt the Holy Spirit continually urging her to “Go, preach the Gospel!”[8] She is the second known Black female preacher and served in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church as an official itinerant preacher. Her bishop would not license her, but he allowed her to preach in Pennsylvania churches.[9] She also preached in New England, across the mid-Atlantic states, and in Canada.[10] At the turn of the century, Black women preached in Methodist and Baptist denominations, and in the Holiness, Pentecostal, and Spiritual movements.

Julia A. J. Foote

Julia A. J. Foote openly spoke against women preaching, but later she said she received and then answered a call from God to preach. As an itinerant evangelist and preacher, she ministered across the U.S. and into Canada for fifty years.[11] The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ) ordained Julia in 1895 as their first woman deacon. Then the AMEZ ordained their first female elder, Mary Snow, in 1898. The following year, this same denomination ordained Julia A. J. Foote as their second female elder.[12] Other Black churches that ordained women ministers during this period were the African Methodist Episcopal (AME, 1948), and the Christian Methodist Episcopal (CME, 1954).[13]

Founders of Churches and Denominations

Some Black women, frustrated by sexism and the refusal of some denominations to ordain women, founded independent churches in the 1920s and 1930s. Rosa Horn founded the Pentecostal Faith Church for All Nations in Harlem.[14] Lucy Smith founded the Chicago-based All Nations Pentecostal Church. And, Ida Johnson founded and served as the bishop of the Mount Sinai Holy Church of America, Inc.[15]

Priests and Bishops

In 1977, Pauli Murray was ordained in Washington D.C. as the Protestant Episcopal Church’s first Black female priest.[16] Twelve years later, Barbara Harris became the first female bishop ordained by the Episcopal Church in Massachusetts.[17]

Conclusion

Though these Black women faced ridicule, rejection, transportation challenges, and even enslavement, the historical record reflects that many Black women won the battle to preach. They acted in faithfulness to “go and make disciples” through what they received as the Holy Spirit’s call to preach, evangelize, and plant churches.

[1] Bettye Collier-Thomas, Daughters of Thunder: Black Women Preachers and Their Sermons, 1850–1979 (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1998), 8.

[2] Collier-Thomas, Daughters of Thunder, 2.

[3] Margaret Fell Fox, Women’s Speaking Justified (1667; repr., Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1979), accessed April 6, 2022, http://www.qhpress.org/texts/fell.html.

[4] Collier-Thomas, Daughters of Thunder, 19.

[5] “By 1920, most mainline Black denominations (with the exception of the Baptists) had a number of women they acknowledged and actively supported as evangelists.” Many male clergy welcomed the services of women evangelists, recognizing their value in building church membership and raising funds.” In Collier-Thomas, Daughters of Thunder, 20.

[6] Collier-Thomas, Daughters of Thunder, 31.

[7] Collier-Thomas, Daughters of Thunder, 42.

[8] Eric Washington, “Jarena Lee,” Christianity Today, May 2017, accessed March 21, 2022, https://wwwwww.christianitytoday.com/history/people/pastorsandpreachers/jarena-lee.html.

[9] Collier-Thomas, Daughters of Thunder, 45. See also Muir, A Women’s History of the Christian Church, 227.

[10] Washington, “Jarena Lee.” See also Collier-Thomas, Daughters of Thunder, 45.

[11] Collier, Daughters of Thunder, 59.

[12] Collier, Daughters of Thunder, 59.

[13] Sandra L. Barnes, “Whosoever Will Let Her Come: Social Activism and Gender Inclusivity in the Black Church,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45, no. 3(2006): 371–87. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3838290.

[14] “Rosa Artimus Horn,” Oxford African American Studies Center, December 2006, accessed April 21, 2022, https://www.oxfordaasc.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.001.0001/acref-9780195301731-e-41715; See also Thomas, Daughters of Thunder, 278.

[15] Thomas, Daughters of Thunder, 278; See also David Michel, “Ida Bell Robinson,” Oxford African American Studies Center, May 2013, accessed April 12, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.37762.

[16] Thomas, Daughters of Thunder, 233.

[17] Rosemary Skinner Keller and Rosemary Radford Reuther, eds. In Our Own Voices: Four Centuries of American Women’s Religious Writing (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1995), 310.