Eugene Peterson on Rest: An interview from my files

The late Eugene Peterson, a pastor for thirty years before becoming professor of spiritual theology at Regent in Vancouver, B.C., wrote many books including a “Koine English” translation of the Bible, The Message. He also wrote works on pastoral ministry—and not the celebrity-pastor kind—such as Under the Unpredictable Plant; Working the Angles; Five Smooth Stones for Pastoral Work; and Subversive Spirituality. Despite his busy schedule, Peterson took a weekly day off. Back in the 1990s, I—then a workaholic—sat down with him and asked him about rest. His words changed me and have retained their relevance:

SG: We live in such a busy world. How do we slow down?

EP: The first thing is that you have to be convinced it’s important. Unless you’re convinced, it’s hard to do. The world is conspiring against you—your pastor most of all. So first I think you have to be convinced it’s true. There’s one book which I think is indispensable for convincing you it’s true—Abraham Heshel’s book, The Sabbath. If you read that book three times, you will think, “There is no way I cannot keep the Sabbath. If I’m going to honor God, I’ve got to keep a Sabbath.” It’s a paperback, inexpensive. If the commandments don’t convince you, which they should, Heshel should do it.

Second, I think you can’t do it by yourself. It’s you against the world. You need help from your family, a friend. You have to add a sense of adaptation to your circumstances. So you’ve got to avoid this all-or-nothing thing. Some people have work that prevents them from doing it. [My wife and I] didn’t start doing this until our children were in school. It took that long for us to “get it.” So I never dealt with the small children thing. But spouses can do this for each other. The Sabbath is a gift. You give each other Sabbaths.

SG: How do you spend your Sabbath?

EP: When I was a pastor, on Monday morning we would hike in the woods. We defined our Sabbath this way: we could do anything, but nothing that was necessary. We would play and we would pray. Anything under the category of play was legitimate; anything in the category of pray was legitimate. When we lived in Maryland, we’d pack a lunch, go to a trailhead, and spend the morning in silence. We took binoculars. At lunchtime we would find a place to eat, and Jan would pray. At the trailhead Jan would read a Psalm. We’d start with a Psalm and then remain silent until lunch. Then we’d talk about the birds we’d seen. We didn’t have structure. In the late afternoon, we’d get home and our kids would arrive. We’d putter. Jan would fix supper or I’d fix supper. I’d fix doorknobs. I like to putter. That’s the way it looked for us.

Now it’s different. Now we worship with a congregation on Sunday, and we pack a lunch. We’re only twenty minutes from the beach, so we walk to the beach and have lunch there. Sometimes we’ll be a little more aggressive and go to the mountains—they’re only a half hour away. It’s essentially a day when you don’t do anything.

SG: Was the silence by design or did it just work out that way?

EP: It was an agreed silence. That was harder for Jan [my wife] than for me.

There are different kinds of silences. There’s silence when there’s just nothing happening. But an intentional silence with someone else is qualitatively different than just not talking. It’s amazing what a difference. You have intimacy where a relationship develops. It’s not like nothing is happening. This is a praying intentional silence, when each of you has silence for three to four hours. I can’t say I am praying consciously, except occasionally, but it was a willingness to just sink into that “beingness” of where you were.

There’s another thing I need to say about the Sabbath: It never gets any easier. I wake up Sunday morning or Monday morning—I’ve been doing this for twenty-five to thirty years now—and I can think of something I want to write. I never write on the Sabbath. That’s hard work to me. I don’t even write notes. I say, “Lord, if you want me to remember that on Tuesday, okay!” But that’s it. It still doesn’t get any easier. I would have thought that the weekly habit of Sabbath would by this time just be a habit, but it’s not. I want to do things. I want to call people. It takes me two or three hours before I say, “Okay, Lord, I quit. It’s your day.” There’s so much I could do.

This is where the whole world conspires against you. But the commandment is pretty clear. He said it twice, but He gave a different reason each time. In Genesis, you do it because God did it, which ought to be a good enough reason. The second reason, in Deuteronomy, is because nobody gave you a day off for four hundred years. If you work on the Sabbath, you make other people work—your spouse, your kids, your associates, your congregation. So it’s social justice.

Back when I was a pastor, I told my church, “I will give you a Sabbath, and in turn, I need your help. I will give you Sunday with no meetings, no committees meeting. On Monday I will take a Sabbath. I want you to feel free to call me any time day or night if you need to. But if something can wait until Tuesday, please wait until then.” In thirty years, I think I had three phone calls on a Monday.

SG: Is it possible to integrate this into the institutional world of seminary life?

EP: Once a year our faculty takes a silent retreat for three days. We gather three times a day and sometimes read aloud to each other. We also have a week at mid‑semester called a reading week. We don’t hold classes, the faculty takes a retreat, and the students get caught up.

Are you resting? How might you minister to others by giving a gift of rest?

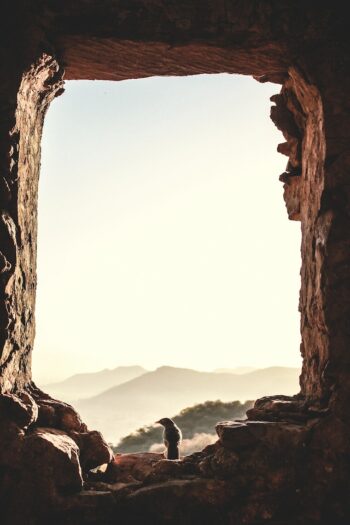

Photo by Abhishek Koli on Unsplash