Hope Even in Suffering

First Peter 3:13–22 is part of the lectionary readings for the sixth Sunday of Easter, May 17th. In verse 9, the apostle alluded to the fact that his readers were being persecuted for their faith. Then, in 3:13–4:19, he dealt more fully with the issue of suffering as believers.

Peter observed that, as a general rule, a devotion to “do what is good” (3:13) should not result in “harm” or punishment. Yet, even if the exception to this rule prevails and undeserved suffering results from doing good, those who belong to the Messiah are “blessed” (v. 14) for being virtuous.

One interpretive option is that Peter’s mention of adversity was a reference to either physical illness or an empire-wide persecution. A more likely option is that the apostle was talking about localized mistreatment from unsaved family members, neighbors, and masters.

Some people are so perverted in their behavior that the virtuous conduct of godly individuals enrages them. The wicked persecute the upright just because they are devout. Yet, the zeal Christians have for doing good can negate any valid reason for unbelievers to mistreat Jesus’ followers.

Others erroneously think that the more pious they become, the easier their lives will be. Yet, Peter, despite his devotion to the Savior, could not avoid either hardship or suffering (Acts 4; 5:17–20, 40–41). The apostle knew that many of the difficulties he endured were the direct result of his godly life.

Peter urged his beleaguered readers not to be intimidated by the “threats” (1 Pet 3:14) made against them from their antagonists. More than anything else, Christians should “revere” (v. 15) or respect the Messiah as “Lord,” for only He is “holy” and deserving of worship. Also, He alone will watch over and protect believers from eternal harm.

The confession, “Jesus is Lord,” was the earliest Christian creed (Rom 10:9; Phil 2:11). Yet, in the first century AD, it could be a dangerous affirmation to make publicly.

In certain periods, the Roman emperor required everyone to confess that he was divine. Christians suffered for insisting, on the contrary, that the Messiah alone is Lord.

Jesus’ followers were to honor Him by acknowledging His supreme authority. Doing this would help them maintain an eternal perspective, especially when they were harassed by others for their faith.

The concept of suffering in Scripture involves physical pain and mental sorrow, along with affliction and agony, brought on by a wide variety of experiences. While God’s Word reveals that some hardship is the direct result of human sin, suffering is also presented as a tool for shaping Christlike character and testing one’s faith (1 Pet 1:6–7; 5:10).

Even Jesus is said to have been shaped by suffering. For instance, in the realm of Jesus’ humanity, suffering made Him whole or complete (Heb 2:10). Also, the hard anvil of daily living tutored the Son in remaining obedient to the will of His heavenly Father (5:8).

Other passages reveal that suffering deepens the reality of the believers’ baptismal union with the Messiah, especially as they experience persecution for His sake (Phil 1:29; 2 Thess 1:5). Paul went as far as noting that adversity is inevitable for those who desire to live in a godly manner as Jesus’ faithful disciples (2 Tim 3:12). Indeed, if the Master suffered, His bondservants must also expect suffering (John 15:18–20).

Peter did not teach that God would always shield His children from adversity. Rather, the apostle assured his readers that God would give them the strength to do what was pleasing to Him.

Amid the reality of suffering, Peter reminded his readers that it was vital for them to be “prepared” (1 Pet 3:15) at any time to “give an answer” (as a defendant would before a judge in a courtroom) for the underlying “reason” of their “hope” in the Messiah.

Hostile questions were prominent in Peter’s mind. If his readers were unprepared when the inquiries came, they might be either speechless or unable to articulate clearly why they had devoted themselves to the Lord.

Some argue that Peter was referring only to formal legal interrogations. Others, however, think he included informal questioning. Either way, the apostle wanted his readers to hold fast to the gospel and courageously proclaim it to others.

As Christians did so, they were to be characterized by humility. Also, as Jesus’ followers spoke about their faith in and devotion to the Savior, they needed to be characterized by “gentleness and respect” (v. 16).

Even though it is impossible to know exactly what suffering the recipients of Peter’s letter had experienced, it is probable that others had subjected them to public insults and injuries. The authorities might have confiscated the property of some and imprisoned others.

Regardless of the hardships these early believers faced, Peter urged them to remain calm and treat their enemies with kindness. Christians could do this knowing that the Lord would eternally bless them.

Furthermore, believers, in giving their testimony, were to maintain a “clear conscience.” Expressed differently, Christians knew that they acted appropriately and were unaware of any guilt.

One’s conscience is the inner faculty that evaluates thoughts and actions. The conscience also bears witness to God’s moral law written on the hearts of all people (Rom 2:15). Admittedly, because the conscience is tainted by sin, it is an imperfect gauge of right and wrong.

The above notwithstanding, the Holy Spirit plays a major role in the believers’ inner ethical dialogue. A Christian who is controlled by God’s Spirit will be able to rightly distinguish between integrity and culpability, as well as between true and false accusations or rationalizations.

Peter stated that the unregenerate would see Jesus’ followers as citizens who obeyed the law and respected the authorities. So, even when Christians suffered without just cause, they “put to shame” (1 Pet 3:16) those who disparaged them as antisocial malcontents.

There are several reasons why the slanderers would be humiliated. People would see that the revilers’ malicious comments were false. Also, the kindness of Christians would contrast sharply with the spitefulness of their antagonists. Moreover, in the day of judgment, enemies of the cross would realize their false accusations were groundless and disgraceful.

Peter stressed that his readers’ good behavior was “in Christ.” By this the apostle meant their commendable conduct was based on their baptismal union with the Savior. He determined what constituted good behavior, and He empowered His followers to act this way.

In verse 17, Peter explained that at times it might be God’s will for His children to endure anguish for “doing good.” The apostle maintained that this was certainly “better” than suffering deservedly due to criminal activity.

Tragically, some Christians grumble when they are treated unfairly and accuse God of injustice. We may not always understand why the Lord allows others to mistreat us, but we should never blame Him for their misconduct.

The apostle directed the attention of his readers to the Savior as the perfect example of enduring unjust maltreatment. Even though the Son was never guilty of any trespass or iniquity, He experienced a horrible death on the cross (v. 18).

Jesus of Nazareth, in taking humankind’s place at Calvary, sacrificially gave His life “once for all.” The “righteous” one made it possible for the “unrighteous” to be reconciled to the Creator. The blessing the Son received for this redemptive act was resurrection from the dead through the Spirit’s power.

Some Bible versions understand verse 18 as a reference to the Holy Spirit physically resurrecting Jesus from the grave. Several New Testament passages also teach that the other two persons of the Godhead played an active role in the Son’s resurrection (John 10:17–18; Acts 2:32; Gal 1:1; Eph 1:20).

Other translations render 1 Peter 3:18 as “made alive in the spirit,” which would be a reference to Jesus’ human spirit. Those who prefer this translation say that Peter was drawing a contrast between Jesus’ flesh and His spirit. According to this line of reasoning, though the Son was bodily put to death, His spirit was made alive by the Father, His body was resurrected, and He entered into the fullness of a glorified human existence.

There are three main interpretations worth mentioning for the identity of the “spirits in prison” (v. 19). First, some think Peter was referring to disembodied spirits of the people of Noah’s day who scoffed at his message and so perished in the Flood (v. 20).

According to the preceding view, the spirits of these individuals are now in Sheol, or Hades, the current residence of the unbelieving dead. Allegedly, the Messiah presented them with a second chance at salvation.

Yet, the above doctrine of a “second chance” finds no clear support in Scripture. Indeed, the Bible teaches that after death the unsaved must face judgment and give an account of their lives to the Creator (Heb 9:27; Rev 20:11–15).

Second, others maintain these spirits are the supernatural beings referred in 1 Peter 3:22. Advocates of this view think these are evil or fallen “angels, authorities, and powers,” related to the “sons of God” in Genesis 6:1–4 (Job 1:6; 2:1; 2 Pet 2:4; Jude 6). However, the direct biblical support for this interpretation seems tenuous, at best.

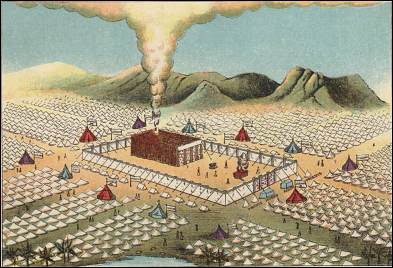

Third, the most likely meaning is that the spirit of Christ (before His incarnation) preached through Noah to the people of his day about an impending cataclysmic event (1 Pet 3:20). Righteous Noah and his family obeyed the Creator by building the ark (amid the insults and ridicule of their neighbors). In contrast, the rest of the people living at that time disobeyed God.

Moreover, because Noah’s peers refused to believe the message he proclaimed, they perished as unrepentant sinners in the Flood (2 Pet 2:5). Consequently, their spirits are now imprisoned and await the final day of judgment at the end of the age. In contrast, as a result of Noah’s faithfulness, the Lord brought Noah and his family safely through the great deluge.

In 1 Peter 3:21, the apostle indicated that the waters of the Flood were a figure of “baptism.” New Testament writers closely associated water baptism with salvation (Acts 2:38; Rom 6:3–4; Eph 5:26; Col 2:12; Titus 3:5; Heb 10:22). Likewise, the early church taught that in conjunction with the proclaimed Word (namely, the gospel), the enacted Word (namely, baptism) is a means of divine grace to bring about a person’s spiritual regeneration (or salvation).

In theological agreement with the above, Peter explained that deliverance from sin is not based on the “removal of dirt from the body” (1 Pet 3:21). Instead, through the means of grace, God bestows the gift of faith on the unregenerate. In turn, they experience both the new birth and the Creator’s unconditional forgiveness (Eph 2:8–9; Jas 1:18).

Peter clarified that those who are united with the Son in the waters of baptism also receive the “guarantee” (1 Pet 3:21) of a “clear conscience” before the Father. Expressed differently, they rest in the assurance of God’s objective, external declaration that He has freely pardoned them of their sin. So, baptism signifies His pledge to us, not our pledge to Him.

Jesus’ atoning sacrifice on the cross (Rom 3:24–25), along with His triumphant resurrection from the dead (Col 2:15), are the basis for the Creator declaring repentant, believing sinners to be not guilty in His sight (Rom 4:25). The Father vindicated the Son’s death when the Father raised the Son from the dead (1:4).

For 40 days, the Savior ministered on earth to His followers (Acts 1:3). Then, He ascended into “heaven” (1 Pet 3:22). Now, Jesus sits at the “right hand of God,” which is the place of supreme power and absolute authority.

The Son reigns forever as co-regent with the Father over all entities throughout the universe. Paul said something similar when he taught that Jesus rules over all forces, authorities, powers, and potentates (Eph 1:20–22).

The next time we are up against a problem that seems unbeatable, we should remember that we serve a risen Lord whose authority encompasses everyone and everything. Nothing in all creation takes the Son by surprise, and nothing can ever separate us from His eternal love (Rom 8:31–39).

Key ideas to contemplate

Suffering and trials often prove too difficult for us to handle in isolation. The situation, however, dramatically changes when we turn to the Lord for wisdom and strength. He is ever-present to journey with us through our most difficult ordeals. This includes providing encouragement and guidance through the caring presence of other believers, who themselves are veterans of encountering and enduring hardship in their lives.

1. Embrace a different view. At first, it seems counterintuitive that any benefit could arise from periods of suffering in our lives as Jesus’ followers. Yet, Peter’s admonitions to his readers challenges us to embrace a different view. Specifically, even amid hardship and anguish, Christians can find legitimate reasons to rejoice.

2. Experience God’s blessing. Peter acknowledged to his readers that, generally, doing good does not result in harm coming to a person. The apostle explained that, even if it does, God can use suffering for Jesus’ sake to bless Christians, along with others who know them.

3. Explain our hope in the Messiah. When believers are slandered for doing what is right, it is natural to become alarmed. Still, Peter encouraged Christians not to fear. Instead, they should take the opportunity to explain their hope in the Messiah, yet with gentleness and respect.

4. Emphasize our salvation in the Son. Peter urged believers, amid circumstances involving suffering, to keep a clear conscience. This includes not retaliating, but praying for and showing compassion to one’s enemies. Christians should also emphasize the enormity of their salvation in the Son and how much of a difference this makes in their lives.