The “image that fell from heaven” in Ephesus (Acts 19:35)

Bonus material: Stuff I discovered while researching my forthcoming book, Nobody’s Mother: Artemis of the Ephesians in Antiquity and the NT:

When the Ephesian silver workers caused a disturbance over the apostle Paul’s ministry cutting into their souvenir trade, the city clerk delivered a speech in which he referenced Artemis’s “image that fell from heaven.” That’s the translation, at least. It’s awkward to render into English, because the Greek has diopetous (διοπετοῦς), “Dio” being the Greek name for Zeus. Literally, the image is “Zeus-fallen.”

Zeus was Artemis’s father. So what exactly was the image to which the clerk referred?

It’s possible the artifact is sitting in storage in the Liverpool Museums!

Arthur Bernard Cook, a British archeologist and classical scholar, best known for his three-part work published in 1940, Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, described an object obtained by one Sir William Ridgeway. The piece, he said, “came through a Mr. H. Lawson of the consular service at Smyrna, together with a miscellaneous lot of arrow-heads and other items from Ephesos.” As Cook tells it, “Sir William acutely detected its [the artifact’s] true character and had intended some day to publish [info about] it as a good example of an aniconic deity. On his death it [the object] was passed on to me by Dr J. A. Venn, President of Queens’, and Mrs Venn, Sir William’s daughter.”[1]

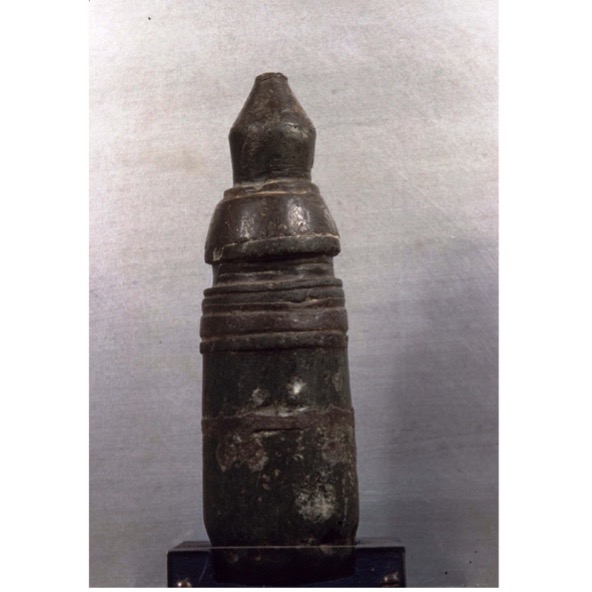

“Diopet” of Ephesus, courtesy of National Museums Liverpool, World Museum

Cook attempted an identification of the piece as “A baitylos (?) from Ephesos, now at Queens’ College, Cambridge”—a baitylos being a sacred stone thought to be endowed with life or given access to a deity, most commonly Zeus. Some such stones were meteorites (or at least thought to be) and dedicated to a god or revered as a symbol of the god itself.

This piece from Ephesus seemed to bear “a possible parallel to the baitylos of Kybele, set in silver and decked with a necklace.” Cook said it was “essentially, a neolithic pounder (6-1/4inches high) of dull green stone,” which had been “subsequently facetted and inlaid with tin,” with the sort of faceting that occurred “sporadically throughout central Europe towards the end of the stone age.” He observed that “it may be inferred on technical grounds that this pounder was decorated ca. 2000 B.C. Several of its features—green.”[3] Okay, that’s a lot of technical info about a stone. Here’s what he considered the ramifications:

“The really remarkable thing about our pounder is the arrangement of its decoration, which transforms the neolithic tool into a quasihuman shape. The head is surmounted by a conical tin cap, secured by three tags or tenons of tin, any one of which might suggest a nose. The shoulders are covered by a broad tin cape. The waist is represented by a deep groove. Below this is a double belt of tin. Lower down, the facetted surface looks like folds of drapery encircled by a tin band, from which hang four pairs of tin pendants symmetrically placed. Finally, at the foot, opposite each pendant is a hole for the insertion of a stud, perhaps of amber or vitreous paste. In short, we may venture to recognise a primitive idol comparable with the bottle-shaped goddesses figured on coins of Asia Minor…. [4] It is therefore tempting to compare this humanised pounder with the ‘Zeusfallen’ image of Artemis Ephesia. And all the more so, when we learn that, by an impressive coincidence, the pounder actually came from Ephesos”[5](emphasis mine).

In 1952, Charles Seltman, a numismatologist (expert in coins), proposed that “Zeus-fallen” in Acts 19:35 referred not to a cult statue, as one might expect, but to some small, additional object—perhaps a Neolithic artifact—which was also sacred and housed in the temple. Additionally, he regarded the temple-shaped headgear of several images of Artemis Ephesia as representations of a small shrine, replicas of which were made by the silversmith such as Demetrios, in which such an object would be housed.[6]

Eight years after Seltman published his article, Kenneth Oakley, an anthropologist, paleontologist, and geologist who dated fossils and worked with the British Museum, learned that Cook had, thirteen years earlier, sold the primitive piece from Ephesus to the City of Liverpool Museums.[7] Oakley received permission for the British Museum’s Natural History department to analyze it. (See photo).[8]

The Museum’s Keeper of Mineralogy at the time confirmed immediately that the piece was not a meteorite, but a terrestrial rock.[9] Subsequently, Oakley learned that someone had already examined the piece petrologically while it was in the Department of Classics in Cambridge. That researcher had provisionally identified it as a form of chloritic schist.[10] That’s a kind of rock. Still with me? Stay with me here.

Oakley noticed the figure was inset with four pairs of tin pendants, symmetrically shaped.[11] He observed that its shape conformed to that of ancient idols, and he classified the piece as resembling ancient Neolithic implements often supposed to have fallen from the sky. He wrote, “It is therefore temping to compare this humanized pounder with the ‘Zeus fallen’ image of Artemis Ephesia”[12] mentioned in the Book of Acts. I didn’t make the connection, friends. He did.

In 1971, writing for Folklore, Oakley told how he thought the Liverpool Museums came to possess the piece: “The Diopet was indirectly recovered from Ephesus by Sir William Ridgeway, but the precise circumstances through which it was found have not been recorded. Professor Jocelyn M. C. Toynbee told me that she thought there was no doubt it was preserved in the temple of Artemis throughout ancient times, until with the conversion of the Roman world to Christianity the cult of Artemis petered out and the temple fell into decay. The late Miss Elaine Tankard while Keeper of Archaeology in the Liverpool Museums made an interesting suggestion as to how the Diopet was placed in the shrine. She said it would have fitted perfectly if worn in the crown of the statue of Artemis as this appears in existing replicas.”[13] Oakley adds that it is indeed by “impressive coincidence” that “the pounder actually came from Ephesos.”[14]

The narrative and findings aligned with Seltman’s proposal that the diopet of Acts referred not to a statue. Rather, it was a small, Neolithic, sacred artifact housed in Artemis’s temple and associated with the statue’s head gear. In LiDonnici’s words, “Seltman regarded the temple-shaped headgear of several images of Artemis Ephesia as representations of a small shrine (replicas of which were made by the silversmith Demetrios) in which such an object would be housed. This is an interesting possibility, especially since it explains the mysterious change to masculine gender for adjectives modifying της μεγάλης ‘Αρτέμιδος (“the great Artemis”).[15]

Whether or not the piece in the Liverpool Museums’ possession is the one to which Luke in his Gospel referred, it affords readers a look at the possibilities of what the city clerk of Ephesus could have meant by a “Zeus-fallen” image. Additionally, the symmetrically placed pairs of tin pendants may provide clues as to the meaning of items on the goddess’s torso (that is, Artemis of the Ephesians’s so-called breasts—they were perhaps shapes borrowed from the diopet).

I contacted the Liverpool Museums, and they offered to take a photo for me. And yes, the museum has it labeled as the “Diopet of Ephesus.” Photo used with permission.

[1] Cook, Arthur B. Zeus: A study in Ancient Religion, vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1940, p. 898.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Cook, 899.

[4] Cook, 900.

[5] Charles Seltman, “The Wardrobe of Artemis,” Numismatic Chronicle, 6th ser., 12 (1952) 33–44.

[6] Warhurst, Margaret, “The Danson Bequest and Merseyside County Museums,” Archaeological Reports (Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies) No. 24 (1977–1978), pp. 85–88.

[7] Oakley, K. P. “The Diopet of Ephesus.” Folklore 82, 3 (1971): 207–11.

[8] Oakley, 207.

[9] That is, greenish rock composed of mineral grains that can be easily split into plates or flakes.

[11] Oakley, 209.

[12] Oakley, 210

[13] Oakley, 210, FN 3.

[14] Oakley, 210. Spellings of the city vary.

[15] LiDionnici, “The Images of Artemis Ephesia,” Harvard Theological Review, 85:4 (1992), p. 395, fn. 27.

One Comment

Pingback: