The Son, worthy to redeem the lost

Title:The Son, worthy to redeem the lost

Aim: To turn to the Savior for help, especially in our times of struggle.

Scripture: Revelation 5:1–14

The worthiness of the Messiah, Revelation 5:1–5

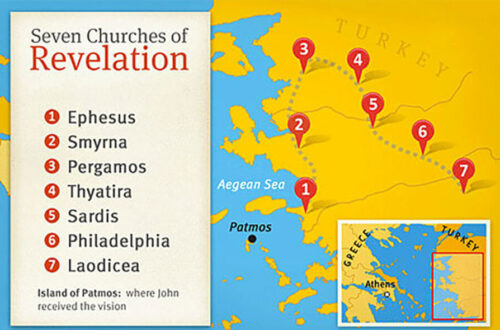

The major literary segments of Revelation have an introductory throne room scene, which lays the foundation for the verses that follow. For instance, the vision of the exalted Messiah recorded in 1:9-20 is a preface to the messages to the seven churches found in chapters 2 and 3.

Likewise, the throne room scene recorded in chapters 4 and 5 is a prelude to the seal judgments. The first six of these are recorded in chapter 6, followed by an interlude in chapter 7, and end with the seventh seal in 8:1.

The material found in 8:2–11:18 follows a similar pattern. The introduction would be 8:2–6, followed by the unleashing of the seven trumpets in 8:7–9:21. An interlude appears in 10:1–11:14, followed by the blowing of the seventh trumpet in 11:15.

Each of the introductory sections has a Christ-centered aim. Specifically, they serve as a continual reminder that the Lamb is fully just in His evaluation and judgment of humankind (Ps. 51:4; Dan. 9:4-14; Rom. 3:3-4).

In the unfolding drama of Revelation, John saw that God held a scroll in His right hand (signifying the place of divine power and authority). This roll of papyrus or leather had writing on the inside and outside, and it was sealed in seven separate places (Rev. 5:1; compare the double-sided scroll in Ezek 2:9–10). This made it inaccessible and impossible for an unauthorized person to open (Isa. 29:11).

When John lived, scrolls usually had writing on only one side and were sealed in one place. The writing on the front and back of the scroll John saw indicates that the decrees of God recorded on it were extensive. The number seven, representing completion or perfection, indicates how thoroughly the contents of the scroll were sealed for secrecy.

There are varying views about the contents of this sealed scroll, including God’s covenant, His law, His promises, and a legal will. The close parallel with Daniel 12:4, however, suggests that the scroll of Revelation 5:1 contained God’s plan for bringing human history to its conclusion.

The document unveiled that judgment was the fate of those who rejected God, while eternal life was the destiny of those who trusted in Him. Put another way, the Son would condemn the wicked and vindicate the upright.

Revelation 6 details the Son’s opening of the seal judgments and with them the unleashing of six (out of seven) devastating judgments on pagan, secular humankind. The idea is that, unless the seals of the scroll were opened, God’s purposes would remain undisclosed and unexecuted.

John saw a mighty angel issue a call for someone to come forward and break the seals, revealing the scroll’s contents (5:2). The celestial emissary did not ask who was talented, influential, or powerful enough. Instead, he wanted to know who was sufficiently “worthy” to perform the task.

The Greek adjective translated “worthy” refers to that which is “fit” or “deserving.” In this context, it denotes both the ability and authorization to execute the divine intention for the consummation of the ages.

Only someone who was infinitely holy and morally perfect could do so. Yet, no one in all of God’s creation responded to the angel’s summons (v. 3).

John was so caught up in this drama that he wept repeatedly when no one came forward to open the scroll (v. 4). He sensed the urgency of the moment, along with the significance of the document.

Amid the apostle’s distress, one of the 24 elders seated around the throne told the apostle to stop weeping. Lamenting was unnecessary, for there was someone who had the virtue and authority to bring history to its divinely foreordained climax (v. 5).

The elder revealed the person who was worthy to take the scroll from God’s hand and open its seals—“the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David.” Both metaphors are familiar Old Testament titles, and together they summed up Israel’s hope for the coming Messiah (Gen. 49:9-10; Isa. 11:1, 10; Jer. 23:5).

God’s people had called Judah—the founder of the illustrious tribe—a lion, and now the elder applied the name to the greatest of all the members of Judah. In ancient times, the lion represented royalty, power, and victory, and these were typified in the risen Messiah.

The Greek noun translated “Root” (Rev. 5:5) describes a shoot or sprout out of the main stem. As the “Root of David,” Jesus is identified as the Messiah who sprang from the house and lineage of David.

The Greek verb rendered “has conquered” means “to win a victory,” “to be a victor,” or “to overcome.” It stresses the completion of the Messiah’s triumph on behalf of the redeemed.

Unlike Rome’s legendary warrior-generals, Jesus did not prevail by being cunning and adroit on a battlefield, but through His atoning sacrifice on the cross and resurrection from the dead (Luke 10:18; John 12:31; 16:33; Col 2:15; Rom 16:20). Also, the verb translated “to open” (Rev 5:5) reinforces the truth that only the Son had the virtue and authority to bring about the fulfillment of the Father’s plan of redemption.

None of us can escape hardships and difficulties in life. Also, these circumstances can both feel overwhelming and challenge the strength of our faith. Just because we are hurting and angry, just because we have doubts or questions, just because we feel less than “spiritual” in our struggles, we do not need to avoid turning the Lord Jesus for help and hope.

In Scripture, the word “hope” renders a term that means “to wait.” In one sense, it is a confident expectation that the Redeemer is present and active in our lives, regardless of what is occurring. This confidence in the Savior’s presence and power gives us the strength to avoid becoming so discouraged that we slip into inaction.

As this week’s Scripture lesson text makes clear, we can also act in the present—despite difficult circumstances—because of what we believe Jesus will bring about in the future. He not only atoned for our sins by dying on the cross, but also rose from the dead.

Moreover, one day Jesus will return to take us to our heavenly home. The Messiah can do this because He is the all-powerful, ever-living Lord.

The worship of the Messiah, Revelation 5:6–14

As the celestial drama unfolded, John did not see a mighty lion, but instead a Lamb that looked as if it had previously been slaughtered. This unexpected, jarring image portrays sacrificial death, thus linking the Messiah to the Old Testament Passover lamb (Exod. 12:5-6; Isa. 53:4–8, 10–12; John 1:29, 36; 1 Cor 5:7; 1 Pet 1:19).

A lamb is a gentle animal, and so suggests one who is approachable. Also, a lamb was a sacrificial animal, and so suggests salvation and forgiveness.

In John’s vision, the Lamb, who bore the marks of death (Rev 5:6), also possessed the symbols of divine power and the abundance of knowledge. The “seven horns” may represent perfect power, and the “seven eyes” may indicate the Lamb’s infinite awareness and sagacity.

John explained that the seven eyes were the “seven spirits of God sent out into all the earth.” Most likely, this is a reference to the sevenfold perfection of the Spirit. His ministry is to exalt the Son, along with making His presence and power a reality to all who trust in Him (John 14:26; 15:26; 16:13–15).

John watched as the Lamb came forward and took the scroll from God’s hand (Rev 5:7). The scene is suggestive of the Messiah being coronated and installed for His royal task. In this way, the Father invested His Son with authority to carry out His plan for the world (Dan 7:13–14).

When the Lamb took the scroll, the four living creatures and the 24 elders around the throne fell prostrate in humility, devotion, and worship before Him (Rev 5:8). Then, in recognition of His triumph over the forces of evil (14:2), they played harps, or lyres, the traditional instruments used in Jewish liturgy to accompany the singing of psalms.

The cohort’s golden bowls full of incense were symbolic of the eternally valuable prayers of the Lord’s holy people (Exod 30:1, 7–8; Ps 141:2; Luke 1:10; Rev 8:3–5). Most likely, these were petitions for the full and final realization of the kingdom of God (Rev 5:8).

The worshipers began to sing a new song, for the Lord was about to inaugurate a new and final phase in the redeemed order of His kingdom (Pss 96:1–2; 144:9–10; Rev 14:3). The participants sang this hymn to the Lamb as Redeemer.

The cohort praised the Son’s worthiness to take the scroll and open its seals. The fact that the Messiah died to atone for the sins of all humankind is evident in the declaration that the redeemed would come from “every tribe and language and people and nation” (Rev 5:9; see Dan 7:14; Rev 7:9).

The result of Jesus’ sacrificial death is that He made His people a kingdom of priests to serve their God. The Messiah would be the rightful Monarch, and His people would comprise His kingdom (Exod 19:6; Isa 61:6; 1 Pet 2:9; Rev 1:6). They would reign with Him forever (1 Cor 6:3; 2 Tim 2:11–12; Rev 2:26; 5:10; 20:4, 6).

John heard the singing of countless numbers of angels around God’s throne (Dan 7:10), along with the voices of the living creatures and of the elders (Rev 5:11). The heavenly choir encircling God’s throne praised the Lamb for His worthiness (Phil 2:10–11).

It was fitting for the Messiah to receive glory, power, and praise for who He is and what He has done. He is the Son of God, whose sacrificial death at Calvary enabled believers to become His bondservants in His eternal kingdom (Rev 5:12).

Two millennia ago, the Lord Jesus set aside His kingly prerogatives, came to earth as a human being, and gave His life so that we might have new life by trusting in Him. The Messiah, of course, did not remain in the grave. He conquered sin and death when the Father resurrected the Son.

Through our baptismal union with Messiah, we are joined with His death and resurrection. This means His victory over the forces of evil also becomes our victory.

Imagine that you’re about to face a period of intense conflict. Where would you go to find comfort, and from whom would you receive strength to handle the trial?

The answer is Jesus the Messiah. He is the fierce Lion of the tribe of Judah who wages war against God’s enemies. Jesus is also the gentle Lamb who has redeemed us through His atoning sacrifice.

John’s vision of the Messiah provides consolation and strength to believers as they endure unimaginable difficulties. Although the Lord’s wrath would fall on the wicked, He would bless the upright with His goodness and grace. Despite the calamity that would eventually overtake the world, God was still orchestrating all the events of history.

John next heard every creature in heaven, on earth, under the earth, and in the sea sing hymns in adoration to the Father and the Son. The idea in verse 13 is that all entities in the entire universe joined their voices to express unending adoration to the Father and the Son. The four living creatures affirmed their praise by declaring “Amen” (v. 14), and the 24 elders responded appropriately by prostrating themselves in worship before the throne.

We live in uncertain times and there are days when the future seems bleak. We should not lose hope, however, for Jesus the Messiah is worthy to take the scroll and open its seals.

The preceding truth means the Father has allowed the Son to carry out the end-time plan for the world. The future is never in doubt, for the Son brings to pass all that the Father has decreed for His children.

For thought and application

The movie Shadowlandsdepicts a portion of the life of Christian writer, C. S. Lewis. It is a significant juncture in his life because up to that point, he held many beliefs about God and the problem of pain that seemed right and good to him. Yet, these beliefs had been relatively untested in his own experience.

The huge blow to Lewis’s faith came when his wife, Joy—a woman whom he had married late in life and with whom he was deeply in love—died of cancer only three years after they were wed. Suddenly, in this great personal loss, Lewis could, at first, only perceive God as impersonal, almost an enemy.

Lewis grappled with the emotions he was experiencing—feelings that defied his faith in God’s goodness. Yet, even in these often angry and sometimes accusing thoughts and feelings, Lewis did not hide from God. Instead, Lewis dialogued with the one who had taken his wife from him, knowing that God was able to handle His bondservant’s struggle and understand all that he was suffering.

As Lewis’ grief took different turns, he could see that this awful experience was not destroying his faith (as he first feared). Rather, it was deepening faith, changing it into a more real and substantial kind of trust.

Many literary critics say that Lewis’s most significant and meaningful work was written after this profound loss and subsequent struggle. No doubt he had found a new level of intimacy and fellowship with the Creator that became evident in what Lewis penned.

C. S. Lewis died in 1963, three years after Joy’s passing away. Lewis’s legacy of faith, however, lives on. It is not a legacy based on theoretical beliefs, but on a genuine trust that turned to the Lord in the worst of times and found that the Savior was there for Lewis.

We also worship and serve the same Redeemer and can turn to Him for help in our times of trouble. These circumstances can not only feel overwhelming, but also challenge the strength of our faith. Yet, even when we are hurting and angry, we can turn to the Lamb for strength in our times of deepest distress.