About Bathsheba…

Today I’m happy to feature Lindsay Ann Nickens, a budding Old Testament scholar at Dallas Theological Seminary, in this guest post about Bathsheba.

Lust, betrayal, shame. These words often come to mind when we hear David and Bathsheba’s story. But 2 Samuel 11–12, where we find their story, is primarily—surprisingly—a war text. The story begins with a spring setting, at a time when kings customarily go to war to enlarge national boundaries and defend territories from invading kings (11:1). The Old Testament describes Yahweh as invested in defending Israel as a place solely devoted to his worship. Yet David chose to stay home during the war season instead of investing likewise (v. 2). David apparently had little to do, so he strolled around on his rooftop.

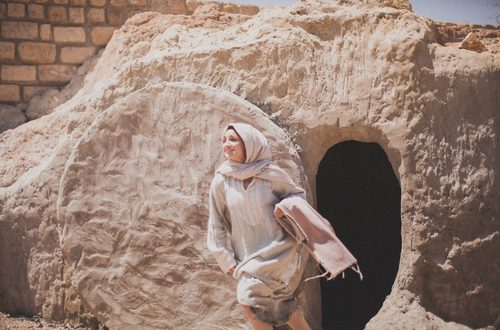

Enter Bathsheba.

Bathsheba was taking a special kind of bath (v. 4)— a ritual performed by Yahweh-worshippers desiring to become ceremonially clean after menstruation (see Leviticus 15:19–20, 28–30). While the biblical text never states that women must ritually bathe post-menstruation, it does state that those in contact with menstrual blood ought to do so, leading to the custom observed here. Women had several bathing options: washing privately in streams, inside fenced-in courtyards, or in homes. Unlike what is popularly depicted in art, there is no indication Bathsheba bathed on her roof, nor would her having done so fit the historical context of the Ancient Near East (ANE). Instead, David saw her as he looked down from the roof of his domain.

David then ordered messengers to “take” Bathsheba, and he proceeded to “sleep” with her. The term used here and in Nathan’s speech to David (12:9) is לקח, meaning to “take” or “seize.” In reference to “taking” a woman as a wife, this term is almost always paired with נשׂא, to “lift up.” Only rarely is it used without נשׂא, such as in when Jacob’s sons state they will not “take” pagans as wives (Gen. 34:16); when the Egyptian king talks about “taking” Jacob’s wife for his own—clearly by force (Gen. 12:19); when Boaz “takes” Ruth and acquires her as a redeemer (Ruth 4:13); and when Michal is “taken” from her husband against her will (2 Sam. 3:15). When “slept” (שׂכב) is used in conjunction with “take” concerning a woman, the pair of verbs is a Hebrew equivalent of our term “rape.” This is clear in Shechem’s actions against Dinah, where he “took” and “slept” with her (Gen. 34:2). What the narrative makes tragically clear, then, is that Bathsheba was bathing herself in preparation for worship of Yahweh when David kidnapped and raped her.

The oft-forgotten piece of this treacherous puzzle is Uriah the Hittite, Bathsheba’s husband. Uriah is listed twice in the Historical Books as one of David’s “mighty men,” a trusted friend and soldier, helping David fight battles, and one who likely helped David escape Saul (2 Sam. 23:39; 1 Chron. 11:41). Uriah’s nationality as a Hittite is a key point in his personality, mentioned throughout 2 Samuel 11 (vv. 3, 6, 17, 21, 24); in Nathan’s speech against David (12:9–10; 1 Kings 15:5; and 1 Chronicles 11:41). Uriah presumably became a circumcised Israelite as an adult, which allowed him to marry Bathsheba and fight in the Israelite army. The title “Hittite” differentiated him from other Uriahs, since the name was not uncommon (for example, Uriah the priest, mentioned in Isaiah 8:2). Uriah probably chose his name upon becoming a Yahweh-fearer, since the name means “Yah(weh) is my light.”

After learning about Bathsheba’s pregnancy, David attempts to convince the visiting Uriah to have sex with his wife. Uriah refuses, stating as his reason that “the ark and Israel and Judah are staying in tents” (1 Chron. 11:11). Staying with the ark during and prior to battle was customary. We see this when David says his men were not sexually active because they were with the ark. Since the ark contained Yahweh’s presence, the same cleanliness requirements of Israelites entering the Lord’s presence to sacrifice were required of those entering battle (1 Sam. 21:2–5). Uriah did not want to risk the ritual uncleanliness of having sex with Bathsheba (Leviticus 18), and thus forfeiting his ability to stay with the ark. Uriah’s decision is particularly interesting when considering his non-Israelite background. War in the ANE was considered a sexual act, with warriors penetrating cities’ gates and flooding cities with soldiers. The spoils of war were equally sexual. Rape was considered the privilege of war heroes (e.g., Judges 5:30), and soldiers raped women and children unable to escape the battle landscape. The ark’s presence in Israel’s battles prevented rape, since the act would have caused a state of uncleanness, prohibiting the individual from remaining with the clean troops. Uriah’s commitment to Yahweh meant refraining from sexual activity with Bathsheba during wartime, which would have had ramifications for his choices in battle.

So David violates Bathsheba and she becomes pregnant. David then sees to it that Uriah gets killed on the battle field, after which he takes Bathsheba as his own wife.

When Nathan confronts David about his sin, he uses war terminology (2 Sam. 12:7–12). Nathan states that David “struck” (נכה) Uriah with the “sword” (חרב) (12:9), a phrase used for action against a city, nation, or national leader (see Num. 21:24, 22:23; Deut. 13:16, 20:13, 28:22; Joshua 8:24, 10:28-29, 11:10-14, 19:47; Judges 1:8, 21:10; 1 Sam. 17:50, 21:10, 22:19; 2 Sam. 15:14, 20:10, 23:10). Using the terms for “struck” and “sword” together, Nathan describes David’s actions as war against a family. Despite David’s absence when Uriah died in battle, Nathan states that David did indeed strike Uriah by the sword, then raped Bathsheba. While Nathan’s comment does not fit the story’s exact chronology, it does fit the wartime ideology of killing soldiers and raping their wives. So, although born a non-Israelite, Uriah honored Yahweh in his refusal to sleep with Bathsheba while David, Israel’s king, raped one of Yahweh’s faithful Israelites.

Yet in a story in which everything is turned upside down, one thing never changes: Yahweh remains a God of grace and justice. Fast forward, and we see Yahweh’s response to David’s sin and Bathsheba’s victimization. Yahweh allows sin to desecrate David’s family just as David desecrated Uriah and Bathsheba’s family. Yahweh places Bathsheba’s son Solomon as king on the throne, ensuring Bathsheba’s safety in old age. And furthermore, Yahweh places Uriah in Jesus’s ancestry (Matt. 1:6), allowing Uriah and Bathsheba’s legacy to permeate a new age. Yahweh sought justice for this faithful couple and caused dire consequences for the king who oppressed them.

But Yahweh was also gracious to David—we might feel uncomfortably so. Though Yahweh ripped apart David’s family from the inside, he remained the God who loves even the loathsome. Yahweh, in grace, allowed David to live and remain as king, even one who was an adulterous murderer, because of David’s repentance. Although it might make us squirm, God loves those who cling to him with broken hearts, both victim and oppressor. As David says after his atrocities, “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and a contrite heart, O God, You will not despise” (Psalm 51:17).

And God does the same for us. He sees us, he loves us. He brings justice where we have been unjust. And he covers us with his grace in our repentance.