Contextualization, Part 2: Making Known the Unknown God

Part two in a series on contextualization from my former intern, Crystal.

“You need more rice.”

I watched my mentor scoop more of the starchy grain onto another student’s plate. We were dining at a Chinese restaurant, courtesy of the head of the research lab where I was interning.

“Chinese people eat a lot of rice. It’s a staple in our culture. Like how Americans eat bread or potatoes.”

Now, I can think of some American cuisines where the meat seems more indispensable. (Have you feasted at a Texas barbeque?) But my mentor’s analogy had served its purpose. My peer’s face lit up with understanding.

Biblical Precedence for Contextualization

My mentor drew from American culture to explain a Chinese concept. It made sense. After all, his research lab resided in the heart of Texas, and my fellow intern hailed from Brooklyn. We were all well-acquainted with American cuisine.

Likewise, the biblical writers and their original audience existed within a particular time and place. The writers of the Hebrew Bible (what we call the Old Testament) inhabited the Ancient Near East. The New Testament writers lived under Roman rule at the height of the Hellenistic period. To communicate concepts about God, the biblical writers drew from the common cultural foundations of their region.

Scripture is rich in contextualization. For the sake of brevity, we will focus on a few examples in which the biblical writers drew from culture to help their audience comprehend theological concepts.

Understanding the World through Myth: An Ancient Near-Eastern Perspective

The Ancient Near-Eastern (ANE) world articulated their understanding of the world through myth, which Richard E. Averbeck defines as imaginative stories that “have a basis in reality and/or history.”[i] As Ancient Near Easterners, the Israelites shared a common cultural foundation with other ANE people groups. To explain theological concepts to their audience, the Old Testament writers drew from ANE mythology.

In Ugaritic myths, Baal assumes kingship after defeating Yam, sea serpent and god of the sea, also known as Litan (Leviathan). The following describes his victory over the serpent:

When you smote Lotan (or Litan), the fleeing serpent, finished off the twisted serpent, the tyrant with seven heads.[ii]

Likewise, Isaiah identifies the serpent as God’s enemy (Isa. 27:1):

At that time the Lord will punish with his destructive, great, and powerful sword

Leviathan the fast-moving serpent, Leviathan the squirming serpent; he will kill the sea monster (NET) (or dragon, ESV) (emphases added).

The psalmist proclaims:

You destroyed the sea by your strength;

you shattered the heads of the sea monster in the water.

You crushed the heads of Leviathan;

you fed him to the people who live along the coast (Ps. 74:13–14, NET)

The parallels are undeniable. In particular, the term “squirming” (“twisting” in ESV) in Isaiah occurs only here in the Hebrew text, suggesting that the writer borrows language from the Baal myth or a common epithet in the ANE world.[iii]

Photo by Caleb George on Unsplash

From Myth to Faith: Pointing People to the One True God

Although the biblical writers drew from the myths of their times, they were not trying to mythologize God. Instead, they presented their Lord as the one true God, sovereign over all. Because ANE myths were well-known to their culture, Old Testament writers drew from them to articulate certain aspects of their faith to their audience. But in the process, they did more than simply retell the myths.[iv] The Old Testament writers repurposed the stories to reveal God’s identity. The prophet and psalmist contextualized the myths within history.[v]

They also implicitly denounced untruths by replacing them with truth. As we’ve discussed, ANE myths portray creation as the product of cosmic battles between gods (see footnote 5). In contrast Genesis 1 features only one God, who creates the world out of nothing. Nothing threatens God’s rule during this process. Evil appears later, in an already created world (Gen 3).[vi]

Drawing from culture to contextualize Scripture thus provides the opportunity to tell the gospel and point people to the one true God. Paul uses this strategy when he explains the identity of the “unknown god” that the people of Athens worshipped….

Acropolis of Athens, photo by Spencer Davis on Unsplash

Making Known the Unknown God

As a Jewish citizen of the Roman Empire, Paul felt at home in both the Greek world and the Hebrew world. His biculturality allowed him to carry the gospel from the Christians of the Hebrew world to the Gentiles of the Greek world.[vii]

Paul took terms associated with Greek religion and philosophy and placed them in the context of Christian faith. For example he redefined “mystery” (mystērion) as referring to God’s plan of salvation (Eph 6:19; cf. 3:1–12) and even to Christ himself (Col 1:26–27; 2:1–3). Paul also declared that God’s “eternal power” and “divine nature” were (and are) visible to all people through creation (Rom 1:19–20).[viii]

Surprisingly, Paul even praised the people of Athens for their devotion to “an unknown god” (Acts 17:22–23). At first glance, it might seem as if Paul is engaging in counteractive syncretism, or syncretism that “directs a person’s primary allegiance to someone or something other than Christ.”[ix] Yet, through a brief exposition of the gospel, Paul quickly proceeded to explain who the people of Athens were worshipping (vv. 24–31). Paul made known the unknown God.

By drawing from the familiar, Paul contextualized the gospel for the people of Athens. As a result, some decided they wanted to hear more. Others, like Damaris, came to faith on the spot (vv. 32–34).

Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash

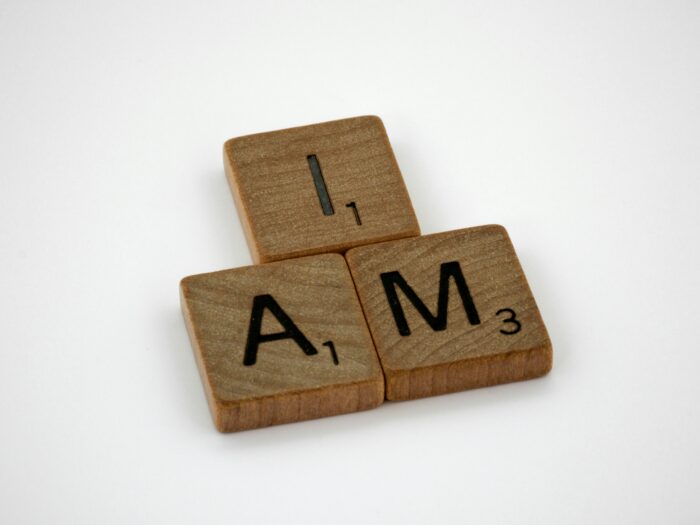

Rice = Bread = ______?

Contextualization is inherently an analogy. It uses a person’s cultural background as a starting point to help them understand theological truths.

Earlier, I told about how a mentor used the analogy of bread and potatoes in American cuisine to describe the importance of rice in Chinese cooking.

Jesus himself contextualized the gospel through seven “I am” statements that built a picture of the essential role that he played (and plays) in believers’ lives. Using terms familiar to a first-century Jewish audience, he called himself “the bread of life” (John 6:35), “the light of the world” (8:12), “door of the sheep” (10:7), “the good shepherd” (10:11), “the resurrection and the life” (11:25), “the way, the truth, and the life” (14:6), and “the true vine” (15:1).

—

This is the second in a three-part series on contextualization. Last time, we examined the difference between contextualization/syncretism and counteractive syncretism through the lens of American Born Chinese. Today, we looked at the biblical precedence for contextualizing our faith. Next, join me for a look at ramifications and applications of contextualization for the church today.

[i] Richard E. Averbeck, “Ancient Near Eastern Mythography as It Relates to Historiography in the Hebrew Bible: Genesis 3 and the Cosmic Battle,” The Future of Biblical Archaeology: Reassessing Methodologies and Assumptions, ed. James K. Hoffmeier and Alan Millard, (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2004), 331.

[ii] Transliteration from Averbeck, “Ancient Near Eastern Mythography,” 337–338.

[iii] Averbeck, “Ancient Near Eastern Mythography,” 339.

[iv] Averbeck, “Ancient Near Eastern Mythography,” 345. For example, the ANE world considered Baal the god who controlled the storm, but many Israelite poems point to God as the one in (true) control of the storm. The psalmist attributes Baal’s title “rider of the clouds” to God (Ps. 68:4), and outright depicts God as Baal (Ps. 29) “from beginning to end” (Carola Kloos, Yhwh’s Combat with the Sea: A Canaanite Tradition in the Religion of Ancient Israel, [Amsterdam: G.A. van Oorschot, 1986], 93). For further discussion, see Robert B. Chisholm, Jr., “The Polemic Against Baalism in Israel’s Early History and Literature,” Bibliotheca Sacra 150 (July–September 1994), 267–283.

[v] Readers of the Bible must beware, however, of reading too much context into Scripture. Illegitimate totality transfer occurs when “meanings and/or implications of terms and expression from various other contexts are illegitimately piled together and forced upon a context where the argument does not call for it” (see fn. 60 in Averbeck, “Ancient Near Eastern Mythography,” 350).

For example, some scholars argue that Genesis 1 echoes the cosmic battle creation motifs of ANE myths. Marduk defeated Tiamat, the deified sea or ocean; Baal subdued Yam, the sea god, before assuming kingship, though not as a creative act (Robert B. Chisholm Jr., “Suppressing Myth: Yahweh and the Sea in the Praise Psalms,” in The Psalms: Language for All Seasons of the Soul, ed. Andrew J. Schumtzer and David M. Howard Jr., [Chicago: Moody Publishers, 2013], 62). In light of the many allusions to cosmic battle in Scripture, some scholars conclude that Genesis 1 echoes ANE creation myths in which the world was created by consequence of a conflict between gods. Some argue that God created the world by defeating Leviathan; others that the world in Genesis 1:2 reflects the ravages of the fall of Satan (Averbeck, “Ancient Near Eastern Mythography,” 348).

Yet, there is no serpentine sea monster or sign of cosmic battle in the biblical creation account. The watery deep of v. 2 (which echoes other ANE creation accounts) simply provides a starting point that the Israelites could understand because of their ANE cultural background (Averbeck, “Ancient Near Eastern Mythography,” 349–350).

[vi] For more examples of the polemical nature of various Old Testament passages, see the discussion in fn. 3 of Chisholm, Jr., “The Polemic Against Baalism,” 268–269.

[vii] William A. Smalley, ed. Readings in Missionary Anthropology II (1978; repr., Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 1986), 370.

[viii] Richard Twiss, Rescuing the Gospel from the Cowboys: A Native American Expression of the Jesus Way, (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books, 2015), 207–208.

[ix] Crystal, “The Gospel in ‘American Born Chinese’: An Introduction to Contextualization,” bible.org, February 13, 2024, https://blogs.bible.org/the-gospel-in-american-born-chinese-an-introduction-to-contextualization/. For further discussion, see Twiss, Rescuing the Gospel from the Cowboys, 35–36.

Crystal holds a Master of Theology degree from Dallas Theological Seminary. A freelance writer and editor, she has the pleasure of helping others tell their own stories. Her passion lies in uplifting vulnerable populations. In her leisure time, you can find her walking her rescue dog, drinking a cup of hot tea, or getting lost in a good book. You can also follow her on X and Instagram @writecrystalc and on her website writecrystal.wordpress.com.