Wood

Long before the dawn of recorded history wood was an essential raw material. It was burned to provide heat and manipulated to provide shelter. Wood is the hard, fibrous substance found beneath the bark in the stems and branches of trees and shrubs. However, practically all commercial wood comes from trees, not shrubs. Since a new tree can be grown where one has been cut, wood is considered a renewable natural resource. (6)

Today in addition to its use as a fuel and as a building material, wood is used in many ways. Although stronger and stiffer materials have been developed over the years, wood is still in great demand. Steel and concrete are the predominant materials used to construct high buildings and long-span bridges, but wood is a major material in houses, low buildings, and short-span bridges. Wood is also widely used in utility poles, railway ties, fence posts, ax and hammer handles, flooring, and paneling. It is also a raw material for pulp-based products such as paper and some plastics, and for turpentine and rosin (see forest products). (6)

Wood, a highly valued resource in the ancient Near East, wood was used for the manufacture of everything from small everyday household items to the palaces of kings and temples and altars of deities. It was especially important as fuel for domestic hearths and industrial installations such as kilns, metal smelters, and forges. (2)

Wood (Hebrew ˓ēṣ, ya ˓ar; Greek. xýlon) was much more plentiful in ancient Israel than in modern Israel. (5) Cooking and heating fires were one of many everyday uses for wood, although deforestation may have required people to search out alternative, cheaper kindling such as dung and thorns. (4) However, in the future this is prophesied to be restored. (Joel 3:18) (5)

Wood consisted of many varieties and was also widely used for construction. (5) Wood is mentioned in many cultic contexts such as the Tabernacle of Moses (1). Acacia wood figures heavily in Exodus, where it is the material for the first Ark (i.e., chest) of the Covenant (for the broken first set and the intact second set of the Ten Commandments) (Deuteronomy 10:1,3,5). The second golden Ark of the Covenant and its carrying poles (Exodus 25:10,13; cf. Exodus 37:1), the golden Table of Show Bread and its carrying poles (Exodus 25:23,28) the supports for the Tabernacle (Exodus 26:15,26,32,37), the Brazen Altar and its carrying poles (Exodus 27:1,6), and the Golden Altar of Incense and its carrying poles (Exodus 30:1,5). (4)

Acacia (Heb: שִׁטָּה, shittah) is a tree species with several varieties that can grow to a height of 20 feet or more, with a trunk up to 2 feet thick. These trees are found in abundance on the Sinai peninsula. Acacia wood is close-grained and is not readily attacked by insects. (15)

Wood was an important commodity in biblical times. Timber was used in the construction of buildings such as Solomon’s temple, which contained a variety of woods including cedar, algum, cypress, and olive wood (1 Kings 6:14–36).

On a larger scale, Solomon contracted with King Hiram of Tyre (2 Chronicles 2:8) imported cedar, cypress, and algum timber (1 Kings 5:10) He built his temple (in fact, the whole temple-palace complex) of stone and cedar (1 Kings 6:9,10,15,16,36; 1 Kings 7:2,3;7:7–12), portions of which were carved (1 Kings 6:18; cf. Exodus 31:5; 35:33); the altar was cedar as well (1 Kings 6:20). (5)(4)

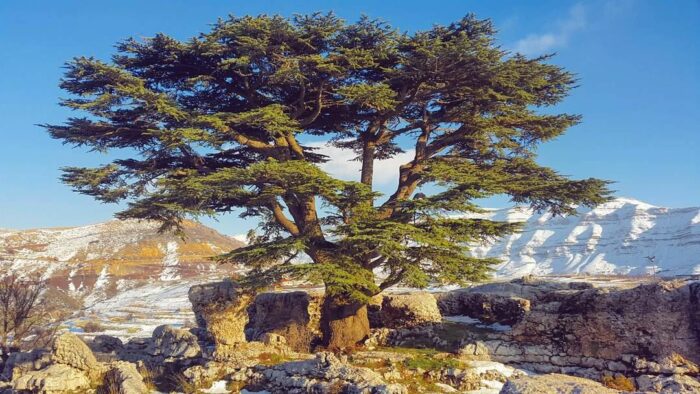

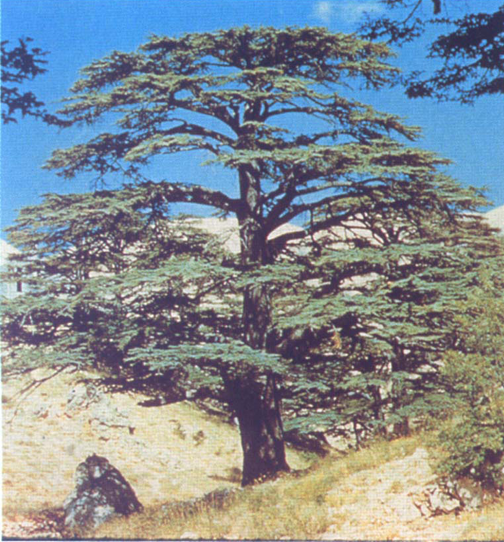

Cedar (Heb: אֶרֶז, erez) are large trees indigenous to Lebanon. Their wood was considered very valuable (e.g., 1 Kings 10:27). Again, cedars were used to build the temple in Jerusalem (1 Kings 5:6, 8), as well as the palaces of David and Solomon (2 Samuel 5:11; 1 Kings 7:2). (16)

The floors he covered with cypress (1 Kings 6:15),

Cypress (Heb: בְּרוֹשׁ, berosh) (Cupressus sempervirens), a kind of tall evergreen found among stands of cedar and oak. Because of their beauty, cypresses were used as ornamental trees in gardens and cemeteries. The hard fragrant wood was preferred for buildings and furniture (Isaiah 44:14, ASB, NRSV: “holm tree”). The fir trees supplied by Hiram of Tyre to Solomon for his temple and palace (1 Kings 9:11) were cypress, as was also the wood for Noah’s ark (Genesis 6:14; KJV: “gopher wood”). Prophets offer metaphorical references to cypress (Hosea 14:8; Zechariah 14:12), and Isaiah uses cypress growth as an image of replenishment and prosperity (Isaiah 41:19;55:13;60:13). (17)

Solomon made supports or steps and musical instruments with the Algum wood,

Algum (Heb: אַלְגּוּמִּים, algummim) or Almug (al´muhg), a special kind of wood, perhaps red sandalwood (Pterocarpus santalinus). Almug was imported from Ophir (southwest Arabia) by Hiram of Tyre and used in the construction of Solomon’s temple, his palace, and for musical instruments (1 Kings 10:11–12). The parallels in 2 Chronicles 2:7-10;9:10–11 have “algum,” perhaps by transposition of two letters. The occurrence of a similar word in Ugaritic (almg) suggests that the spelling in Kings is preferred. (19)(20)

and the cherubim in the inner sanctuary, that housed the Ark of the Covenant, and two inner doors were carved olivewood with the two outer doors were carved cypress (1 Kings 6:23;6:31-35). (5)

Olive Tree (Heb: זַיִת, zayith). A common tree in the Mediterranean world, used for its fruit and especially for the production of oil. It is mentioned frequently in both literal (e.g., Genesis 8:11; Deuteronomy 8:8) and symbolic contexts. Figuratively, it usually represents beauty or God’s blessing (e.g., Psalms 52:8; Jeremiah 11:16; Hosea 14:6; Romans 11:24). (18)

Furthermore, Zerubbabel’s temple (Haggai 1:8) contained wood, and Ezekiel’s future temple (Ezekiel 41:16–26) is to contain wood in its construction. (5)

So extensively is wood employed in the temple that it is proudly noted that “no stone was to be seen” (1 Kings 6:8–20). The quality and quantity of these woods are described in a manner suggesting richness befitting the palace of the King of Heaven (cf. 1 Chron 22:14; 29:2). The choice and aromatic wood of the cedar of Lebanon is so synonymous with the Solomonic temple that “Lebanon” becomes a metaphor for the temple and its glory (Psalms 92:12–13; Isaiah 60:13; Jeremiah 22:23; Ezekiel 17:3,12). So it is no surprise that Ezekiel envisions the new temple with thresholds, windows, galleries-everything-covered with wood (Ezekiel 41:16) and furnished with a wooden altar (Ezekiel 41:22). (3)

In addition, wood was used for more common dwellings (Leviticus 14:45), as well as vessels (Exodus 7:19; Leviticus 15:12; 2 Timothy 2:20). Branches could be used for huts, and lumber provided supports for the walls, roof, doors, and windows. Carts and litters were also made of wood (1 Samuel 6:14). (4) Sturdy poplar and oak were favored for implementing hafts and roofing. The very light wood of the palm had a broad range of uses. (2) Wood was also material for agricultural implements (2 Samuel. 24:22), household vessels (Leviticus 15:12), and seafaring vessels. (4) Wood was used for weapons (Numbers 35:18; Ezekiel 39:9–10), threshing sledges, and ox yokes (2 Samuel 24:22). Almug wood used for musical instruments (1 Kings 10:12) and ebony wood (Ezekiel 27:15) were imported. (5)

A primary and ongoing need of wood was for fuel, both for cooking and heating (cf. Deuteronomy 29:11; Joshua 9:21–27) and for sacrificial fires and burnt offerings (Genesis 22:3–9; Leviticus 1:1-14 passim; Numbers 19:6; 1 Samuel 6:14; 1 Kings 18:23,33,38), particularly for the fire on the tabernacle altar that must never go out (Leviticus 6:12). (5)

Sadly, one all too frequent use of wood was in the making of idols. (5)

Wood Typology

Wooden Idols

If wood takes an honored place in the sanctuary and on the altar and is even covered with gold, it is never to be carved into the image of a god and worshiped. In the context of Israel’s worship, artistry and craftsmanship in wood are only for directing human hearts to worship God in his sovereign majesty and glory. Like the trees of the field that clap their hands and sing, wood is to celebrate God’s glory and not receive it. (3)

The Old Covenant roundly condemns and ridicules wooden idols as the epitome of human folly. The trajectory of this biblical satire begins with Deuteronomy’s warning against falling into idolatry and worshiping “gods of wood and stone, which cannot see or hear or eat or smell” (Deuteronomy 4:28;28:36,64;29:17; Judges 6:25,26; Psalms 115:4-8;135:15-18; Daniel 5:23; Ezekiel 20:32; Habakkuk 2:18,19; Isaiah 37:19;44:9-20;46:6,7; 2 Kings 17:15;19:18; Jeremiah 2:27,28;10:3-15;51:17,18; Acts 17:24-31. Revelation 9:20). The living, merciful and powerful God of Israel who has delivered his people from Egypt is contrasted with pagan idols shaped of lifeless, dense, obtuse material, unresponsive to prayer and sacrifice. This satiric imagery has no time for whatever theology may have informed the pagan understanding of the relation between the idol and its spiritual reality. It fastens its ridicule on the observable phenomena. (3)

The imagery echoes in Hezekiah’s prayer: the gods of the nations overthrown by the Assyrians were cast into the fire and consumed “for they were not gods but only wood and stone, fashioned by men’s hands” (2 Kings 19:18; cf. Isaiah 37:19). But Yahweh is the living God who will deliver. The prophets, particularly Isaiah, most memorably develop the imagery of a wooden idol. A man “selects wood that will not rot” and looks for a craftsman to make an idol that will not topple (Isaiah 40:20). A man cuts down a cedar or cypress or oak or pine. Half the wood he burns in a fire, preparing a meal, roasting his meat, warming himself—all of these are good and fitting uses of wood—but the remainder is used for an idol! (Isaiah 44:13–20). To the wooden god he bows down and says, “Save me; you are my god” (Isaiah 44:17). “No one stops to think … ‘Shall I bow down to a block of wood?’ ” (Isaiah 44:19). (3)

The irony is shocking if not comical and echoes through the prophetic texts, spinning off fresh nuances. “They say to wood, ‘You are my father,’ and to stone, ‘You gave me birth’ ” (Jeremiah 2:27. Israel has “committed adultery with stone and wood” (Jeremiah 3:9). Israel wants to be like the nations, “who serve wood and stone” (Ezekiel 20:32). Belshazzar praises “gods of silver and gold, of bronze, iron, wood and stone, which cannot see or hear or understand” (Daniel 5:4, 23). The wayward people of God “consult a wooden idol and are answered by a stick of wood” (possibly an oracular device such as lots; Hosea 4:12 NIV). Israel’s apostasy is epitomized in the one “who says to wood, ‘Come to life!’ Or to lifeless stone, ‘Wake up!’ ” (Habakkuk 2:19 NIV). And the prophetic imagery is reborn in Revelation as the survivors of the sixth trumpet judgment are unrepentant and continue to worship “idols of gold, silver, bronze, stone and wood—idols that cannot see or hear or walk” (Revelation 9:20, let alone save them from destruction. (3)

Wood and Offerings

Wood is associated not only with the architecture and furnishings of worship but with the fire of sacrifice. In the story of Abraham and the sacrifice of Isaac, we find the woodcut by Abraham and carried by Isaac. And when Isaac is placed on top of the wood and the knife is in Abraham’s hand, the tension of the story reaches its climax (Genesis 22). Wood is a vital part of the sacrificial imagery of the Old Covenant, and the wood burned on the altar is repeatedly mentioned in Leviticus, though it is not described. We can well imagine the great quantities of wood that were cut, hauled, stacked, and kindled during temple festivals, though the Old Covenant barely alludes to this reality (Joshua 9:1-27 (Gebeonite Woodcutters). Nehemiah 10:34; 13:31). (3)

In a few Old Covenant stories, the wood for a sacrifice is an object of interest: the wooden Asherah pole cut down by Gideon (Judges 6:26), the wood of the cart bearing the ark of the covenant (1 Samuel 6:14), the wood of the threshing sledges and the yokes of oxen used for the burnt offerings on the threshing floor of Araunah (2 Samuel 24:22; 1 Chronicles 21:23), the wood arranged on Elijah’s altar on Mt. Carmel, drenched with water and then consumed by fire (1 Kings 18). Wood is consumed by fire along with the sacrifice. It is the divinely appointed fuel for sacrifices and offerings that are to be burned before God, the catalyst and propellant for the sweet savor that ascends to heaven. It is an agent of the symbolic reversal of the human condition of sin, guilt, and an unthankful heart. (3)

Within the pages of the Old Covenant, wood is an ordinary material, a resource of the natural world that is put to holy purpose with little attention to its source or type. As to its purity or impurity, we only read that wood, along with cloth, leather, and sackcloth, is rendered unclean by contact with a corpse (Leviticus 11:32) and must be purified (Numbers 31:20). Only cedarwood, along with scarlet yarn, hyssop, and birds, is specially prescribed for a sacred rite, the cleansing of a leper (Leviticus 14:4–6) or a “leprous house” (Leviticus 14:48–57).

Wood as Judgment

Wood with fire can also form an image of judgment. Isaiah speaks of Topheth, an idolatrous high place in the Valley of Hinnom outside Jerusalem, as a fire pit with abundant wood ready to be set ablaze by the Lord as the funeral pyre of the king of Assyria (Isaiah 30:33). Or God can promise Jeremiah, “I will make my words in your mouth a fire and these people the wood it consumes” (Jeremiah 5:14 NIV). For Ezekiel, the people of Jerusalem are as a vine to any other wood, good only for the fire: (3)

The word of the Lord came to me: “Son of man, of all the woody branches among the trees of the forest, what happens to the wood of the vine? Can wood be taken from it to make anything useful? Or can anyone make a peg from it to hang things on? No! It is thrown in the fire for fuel; when the fire has burned up both ends of it and it is charred in the middle, will it be useful for anything? Indeed! If it was not made into anything useful when it was whole, how much less can it be made into anything when the fire has burned it up and it is charred? “Therefore, this is what the sovereign Lord says: Like the wood of the vine is among the trees of the forest which I have provided as fuel for the fire—so I will provide the residents of Jerusalem as fuel. I will set my face against them—although they have escaped from the fire, the fire will still consume them! Then you will know that I am the Lord, when I set my face against them. I will make the land desolate because they have acted unfaithfully, declares the sovereign Lord.” (Ezekiel 15:1–8 NET)

Ezekiel is to pile wood beneath a pot, heap it on and kindle the fire to cook the bones of a sheep, for Yahweh to pile the wood high for the city of bloodshed, Jerusalem (Ezekiel 24:5–10). (3)

For Isaiah, Assyria is only a wooden weapon of judgment in God’s hand. Once God has accomplished his work in Jerusalem, he will do with Assyria as he pleases, and Assyria will not control God. An ax or rod or club does not wield or brandish the arm that swings it, and neither will Assyria swing the arm of God “who is not wood” (Isaiah 10:15) (3)

Gathering Firewood

Cutting and collecting firewood is a toilsome task even when wood is abundant. Viewed over the full course of the biblical narrative, the Sabbath is a day of rest that foreshadows the final day of rest when the toil of gathering wood will be no more. Its sanctity is shockingly underscored when a man found gathering wood on the Sabbath is put to death (Numbers 15:32–36). The image of an “alien” serving in Israel as a domestic servant is memorably evoked in the KJV wording of “the hewer of thy wood” and “the drawer of thy water” (Deuteronomy 29:11). The poverty and vulnerability of a widow are epitomized as she gathers a few sticks to cook the last of her food (1 Kings 17:10–12). The good days, when families of means had domestic servants and when fuelwood was in plenty, serve as a backlight for images of judgment and affliction in which “wood can be had only at a price” (Lamentations 5:4), “boys stagger under loads of wood” (Lamentations 5:13) and children gather wood while fathers light the fire (Jeremiah 7:18). But on the far side of judgment, Ezekiel envisions a day when Israel will have no need to gather wood from the fields or cut it from the forests, because abandoned and useless wooden weapons—shields, bows, arrows, war clubs, and spears—will serve as fuel (Ezekiel 39:10). (3)

Miscellaneous Wood Typologies in the Bible

An assortment of images of wood is also found in the Bible. Leviathan is so mighty and awesome that he treats iron like straw and bronze like rotten wood (Job 41:27). The everyday reality of wood fueling flames informs two proverbs on quarrelsomeness: “Without wood a fire goes out; without gossip, a quarrel dies down” (Proverbs 26:20); “As charcoal to embers and as wood to fire, so is a quarrelsome man for kindling strife” (Proverbs 26:21). Particular woods evoke wealth and power. Cedar is a wood fit for kings, and so in the Song of Songs, the lover sees her beloved splendidly escorted in a carriage of wood from Lebanon (Song 3:9). Tyre is imaged as a magnificent ship constructed of the best woods: pine for timbers, cedar for mast, oak for oars, and cypress for decking (Ezekiel 27:6). (3)

But in the grading of material for building and craftsmanship, wood takes a place in the lower echelon. In Isaiah’s vision of the new creation, the nations will bring to Zion gold instead of bronze, silver in place of iron, bronze instead of wood, iron in place of stones (Isaiah 60:17). Paul sees disreputable contractors building on the foundation for God’s new temple; the work of those who build with gold, silver, costly stones, wood, hay, or straw will be revealed on the last day (1 Corinthians 3:12). In the context of a household, and in the household of God, wood is useful but common: there are vessels of gold and silver, but also wood and clay; some for noble purposes and some for ordinary purposes (2 Timothy 2:20). (3)

Wood participates in an image of salvation when Noah’s Ark, constructed of gopher wood (possibly Cypress), saves his family and creatures from the Flood. Wood also serves as an image of reversal when Moses casts wood into bitter water and makes it sweet (Exodus 15:22-27), and when Elijah throws a branch into the Jordan and a lost axhead floats to the surface (2 Kings 6:1–7). In the prophecy of Ezekiel, Ephraim and Judah are represented by two sticks of wood that are miraculously joined into one stick representing the restoration of Israel. (3)

In addition, wood also occurs in a figurative sense, often to represent God’s people (Jeremiah 5:14 [to be “devoured”]; Lamentations 4:8 [“dry skin”]; Ezekiel 15:2–6 [allegory of the vine]; Luke 23:31 [a proverb]; 1 Corinthians 3:12; 2 Timothy 2:20–21). (5)

Wood Branches

Various Hebrew words are translated as “branch” or “shoot.” The most common one (tsemakh) can be defined as any sprout of vegetation (Genesis 19:25; Ezekiel 16:7; Psalms 85:11). Branches in the Bible refer either to trees or vines. While the overwhelming preponderance of references is symbolic, the symbol, as always, is rooted in the physical properties of the thing itself. At a literal, physical level, branches are a picture of a healthy and productive tree or vine. The branch is linked to either the solid trunk or main stock that nurtures and anchors it or the leafy outgrowth that springs from it. In the butler’s dream that Joseph interpreted, a vine’s three branches leaf out miraculously into clusters of ripened grapes, an image of fertility and abundance (Genesis 40:10-13). In 2 Samuel 18:9–15, Absalom is caught by his hair in the branches of a tree and subsequently killed by Joab. Jeremiah had a vision of a branch of an almond tree, which signified that God was watching over God’s word, to perform it (Jeremiah 1:11–12). (19)

In the exuberant picture of nature’s provision in Psalm 104, the birds are pictured as living and singing in the branches of the trees that grow by streams (Psalms 104:12). The evocativeness of the branches of a healthy tree is captured by the reference in Ezekiel 19:10 to a vineyard “fruitful and full of branches by reason of abundant water” (RSV). (14)

Mainly, though, branches provide a rich array of symbols in the Bible. In a land with regions where trees were a relative rarity, a healthy tree with strong branches readily became a symbol of strength and prosperity. If leafy, fruit-bearing branches indicate a prospering olive, vine or fig tree, they readily become a symbol for a human family: “Joseph is a fruitful bough, a fruitful bough by a spring; his branches run over the wall” (Genesis 49:22 RSV). Nations too, and especially their rulers, are referred to as trees. Pharaoh, king of Egypt, is told to consider Assyria like “a cedar in Lebanon, with fair branches and forest shade.… All the birds of the air made their nests in its boughs; under its branches, all the beasts of the field brought forth their young” (Ezekiel 31:3, 6 RSV). But because the tree became proud of its towering height, “its branches will fall, and its boughs will lie broken” (Ezekiel 31:12). Psalm 80 pictures Israel as a vine brought by God out of Egypt, whose mighty branches covered mountains (Psalms 80:10). Tragically the vine had been cut down and burned. (14)

Just as the branch full of leaves and fruit is an archetype of abundance and blessing, the broken or fruitless branch is an emblem of ruin and God’s disfavor. When one of Job’s counselors paints a portrait of the fate of an evil person, one of the details is that “his branch will not be green” (Job 15:32), while another counselor asserts regarding the wicked that “his branches wither above” (Job 18:16). Nebuchadnezzar’s downfall is pictured as a tree that is hewn down, with its branches cut off and with birds fleeing from its branches (Daniel 4:14). Extended to a national level, the image yields a picture of the Lord cutting off “palm branch and reed in one day” (Isaiah 9:14) and hewing away “the spreading branches” of trees (Isaiah 18:5; see also Jeremiah 11:16 and Ezekiel 15), while a nation in decline is compared to four or five pieces of fruit on the branches of a fruit tree (Isaiah 17:6). Again the day is coming when God will burn up evildoers and “leave them neither root nor branch” (Malachi 4:1). (14)

But if branches figure prominently in the oracles of judgment, they are also present in the Old Covenant visions of coming restoration. The day will come when “the branch of the Lord shall be beautiful and glorious, and the fruit of the land shall be the pride and glory of the survivors of Israel” (Isaiah 4:2). Israel restored will be like a transplanted cedar that brings forth boughs and bears fruit (Ezekiel 14:22–23). (14)

A cluster of branch images might be termed ceremonial. The Old Covenant Feast of Booths included the ritual of residing for seven days in makeshift booths made from the branches of leafy trees (Leviticus 23:40; Nehemiah 8:15). The mysterious “two anointed who stand by the Lord of the whole earth” are pictured as the “two branches of the olive trees” on the right and left of a lampstand (Zechariah 4:12–14 RSV). Palm branches were cut down and spread on the road in front of Jesus during the triumphal entry into Jerusalem (Matthew 21:8; Mark 11:8; John 12:13) as part of a victory ritual. (14)

The ability of a branch to sprout from the stumps of some types of trees makes it a symbol of rebirth. In Job 14:7–9, the case is put that “there is hope for a tree, if it be cut down, that it will sprout again” and “put forth branches like a young plant” (RSV). As noted above, this rhythm underlies the references to the branch in the prophetic visions, where the tearing down of branches is regularly balanced with visions of branches restored or planted in the oracles that predict a coming messianic age. (14)

When we come to the New Covenant images of the branch, we move in quite a different world. Here the focus is on the functional side of branches and what that can tell us about salvation. Most famous of all is Jesus’ discourse about his being the true vine (John 15:1–6). Drawing on familiar practices of husbandry, Jesus pictures himself as the true vine and his followers as branches dependent on the main vine. Bearing fruit depends on remaining united to Jesus the main vine. Any branch that does not bear fruit is pruned so that it may bear fruit. Anyone who does not abide in the true vine withers and is cast onto a pile of branches destined for burning. (14)

Romans 11:16–24 elaborates the image in a similarly extended way, this time to picture the relationship of the salvation of Gentiles to the Jewish religion. The unbelief of the Jews is likened to branches that are broken from a cultivated olive tree. Gentile belief is portrayed as branches from a wild olive tree grafted onto the cultivated olive tree. Jews who come to believe will likewise be grafted back onto the cultivated olive tree. (14)

People spread leafy branches on the road in front of Jesus when he enters Jerusalem on a donkey (Mark 11:8). Jesus says that just as a leafy branch indicates summer is near, so the warnings he has given should be signs that the end is at hand (Mark 13:28). (19)

We may note, finally, Jesus’ parable in which he pictures a mustard plant that becomes a tree, “so that the birds of the air come and make nests in its branches” (Matthew 13:32; cf. Mark 4:32; Luke 13:19). The fantastic size of the mustard “tree” is offered as a picture of the expansive promise of the kingdom of heaven (1). (14)

As we survey the image of the branch in Scripture, it is obvious that it appears most often in the prophetic visions, as an oracle either of judgment or of coming salvation. In the Bible, the image inherently tends toward symbolism, and its treatment is often imaginative and fantastic, with branches being given qualities and a magnitude that literal branches do not possess. (14)

A Burning Bush

The call of Moses to be Israel’s deliverer took place when he turned to see the marvel of the thorny bush which burned and yet was not consumed (Exodus 3:3. Mark 12:26,27. Luke 20:37. Acts 7:30-35). (The Hebrew סְנֶה (seneh), used elsewhere at Deuteronomy 33:16 and 1 Samuel 14:4, indicates that it was a kind of bramble or thorny bush.) (25) Like all such manifestations which the Bible records (e.g. the smoking-flashing oven (Genesis 15:17) and the cloudy-fiery pillar (Exodus 13:21), the burning bush is a self-revelation of God. (21) Association of clouds, fire, and smoke with the manifestation of God’s glory is a common biblical theme (see also Exodus 19:18; 1 Kings 8:10–11; 2 Kings 1:12;2:11; Is 6:1–6; 2 Thessalonians 1:7; Revelation 1:14;19:12). (23)

The story commences by saying that ‘the angel of the Lord appeared to him’ (Exodus 3:2); the Hebrew translated ‘in a flame’ more aptly signifies ‘as’ or ‘in the mode of’ a flame (Exodus 3:2); Moses (Exodus 3:6) ‘was afraid to look at God’ (Exodus 3:6); Deuteronomy 33:16 speaks of ‘him that dwelt in the bush’. The revelation thus conveyed may be summarized in the three words ‘living’, ‘holy’ and ‘indwelling’:

- The bush is not consumed because the flame is self-sufficient, self-perpetuating.

- Equally, and by a consistent symbolism (e.g. Genesis 3:24; Exodus 19:18), the flame is the unapproachable holiness of God (Exodus 3:5). (21) That God reveals himself as a fire is an image of His holiness. Fire is often pictured biblically as a purifying and refining instrument of God’s holiness. (24) Furthermore, Exodus 3:5 contains the command for Moses to remove his sandals, “for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” (cf. Joshua 5:15.)This incident contains the first direct statement in the Bible linking holiness with the very life of God and making fire the symbol of that holiness. (22)

- Lastly, so as to reveal the sovereign grace of God who, though self-sufficient, freely chooses and empowers instruments of service, the flame in the bush declares that the living, holy God is the Indweller. (21)

The burning bush was a theophany, a visible revelation of God’s glory. The paradox of a plant burning without being consumed provided the means by which God spoke saying, “I Am that I Am” (Exodus 3:14) Meaning He is the same I AM (YAHWEH) that was the I AM (YAHWEH) God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

That God reveals himself as a fire is also an image of his glory. This particular self-revelation of God should not be seen primarily as something designed to produce fear-though understandably it does so (Exodus 3:6)—for the fire is not consuming (though it certainly could be, see Deuteronomy 4:24;9:3, Hebrews 12:29). Rather the burning bush is meant to convince Moses of the majesty of God and to stand as a visible reminder in the many dark times ahead. Thus it is no accident that this act of God’s self-revelation takes place at Sinai, where God would soon reveal his holiness and glory to the entire nation of Israel. (24)

Unlike the gods of Egypt, who were pictured as living in gloomy darkness, Israel’s God revealed himself as one who “dwells in unapproachable light” (1 Timothy 6:16). Moses experienced God’s presence and received the commission to return to Egypt and lead the people of Israel out into the Promised Land. The burning bush evidently symbolized his intent not to consume or destroy his Hebrew people, but to be their savior to lead them out of the bondage of slavery in Egypt and into the Promised Land. (23)

Cedarwood, Hyssop, and Scarlet Wool

King Solomon produced books describing the largest (cedar) to the smallest (hyssop) in the field of botany at that time.

He produced manuals on botany, describing every kind of plant, from the cedars of Lebanon to the hyssop that grows on walls. He also produced manuals on biology, describing animals, birds, insects, and fish. (1 Kings 4:33 NET)

Cedarwood

Cedar signified royal power and wealth (1 Kings 10:27). Thus the evergreen cedar symbolized growth and strength (Psalms 92:12; cf. Ezekiel 17). (7)

Hyssop

A plant used for ritual cleansing purposes, a humble plant springing out of the wall (1 Kings 4:33), in extreme contrast to the cedar. (8)

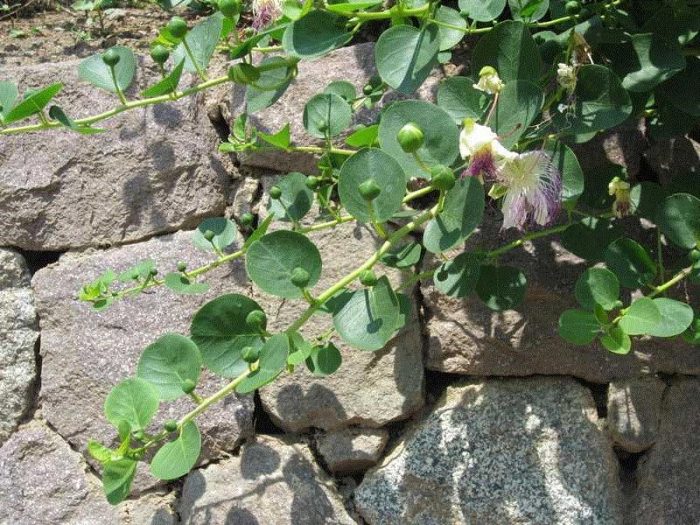

After a careful examination, Dr. Royle has come to the conclusion that the hyssop of the Bible is the caper-plant (Capparis spinosa of botanists); that the name of the plant in Arabic, azaf, corresponds with the Hebrew esobh; and that the shrub is fitted for all the purposes mentioned in the Scriptures. (12)

“The caper-bush belongs to the natural order Capparidaceæ or the Caper family. The plants of this order have pungent, stimulant, and antiscorbutic qualities. The caper-bush grows in Lower Egypt, in the deserts of Sinai, and in Palestine. The localities in which the plant delights are barren soils, rocky precipices, and the sides of walls. The caper plant grows on walls in many southern countries. I have gathered it on walls in Italy. Tristram saw it hanging from the walls of Jerusalem and steep rocks in the gorge of the Kidron. He also says that the variety called ægyptiaca has a trailing habit on the sandy plain between Jericho and Jordan, as well as at the southeast end of the Dead Sea and on the plains of Shittim.” (12)

אֵזוֹב (ʾēzôḇ, “hyssop”) occurs ten times in the OT. (“Hyssop appears twice in the New Covenant: in John 19:29, as the instrument for lifting the vinegar to Jesus’ lips when he was on the cross, and in Hebrews 9:19–20, where the people and the book are sprinkled with blood… Seven OT references are found in two rituals: cleansing a leper (Leviticus 14:4, 6, 49, 51, 52) and cleansing those defiled through contact with the dead (Num 19:6, 18). The other three references are the Passover (Exodus 12:22), King Solomon’s wisdom (1 Kings 4:33), and King David’s prayer for cleanings (Psalms 51:7). (11)

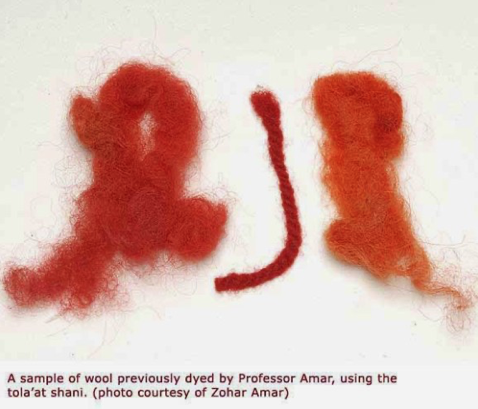

Scarlet (Red) Wool

“I am the good shepherd. I know my own and my own know me—just as the Father knows me and I know the Father—and I lay down my life for the sheep. I have other sheep that do not come from this sheepfold. I must bring them too, and they will listen to my voice, so that there will be one flock and one shepherd.(John 10:14–16 NET)

In Hebrew, the word for red is “Adam” or “Edom.” Adam is one of the words for “man” and literally means “red-blooded man.” It is derived from the root word in Hebrew for blood: “Dam.” The wool comes from sheep, and mankind is often likened to sheep in the Old and New Covenants.

Come, let’s consider your options,” says the Lord. “Though your sins have stained you like the color red, you can become white like snow; though they are as easy to see as the color scarlet, you can become white like wool. (Isaiah 1:18 NET)

Consequently, wool-dyed red topologically represents the sins of mankind.

Cedarwood, Hyssop, and Scarlet Wool Combined

Cedarwood, Hyssop, and Scarlet Wool taken together with the “Whole Burnt Offering” of a specific animal (1), that included its blood and dung, symbolically represent mankind’s works from the grandest (cedar) to the humblest (hyssop) are sinful (scarlet wool) and repulsive (dung) before God and must be covered by blood and then burned until nothing but ashes remain from the fire of His judgment!

We are all like one who is unclean, all our so-called righteous acts are like a menstrual rag in your sight. We all wither like a leaf; our sins carry us away like the wind. (Isaiah 64:6 NET)

A man must believe he is lost before he can be saved. One reason why many are not saved is because they do not believe they are lost. They fold their filthy rags of self-righteousness about them, instead of acknowledging that they are miserable sinners. D. L. Moody (9)

More than that, I now regard all things as liabilities compared to the far greater value of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord, for whom I have suffered the loss of all things—indeed, I regard them as dung!—that I may gain Christ, and be found in him, not because I have my own righteousness derived from the law, but because I have the righteousness that comes by way of Christ’s faithfulness—a righteousness from God that is in fact based on Christ’s faithfulness. My aim is to know him, to experience the power of his resurrection, to share in his sufferings, and to be like him in his death, and so, somehow, to attain to the resurrection from the dead. (Philippians 3:8–11 NET)

The Branch

Listen now, Joshua the high priest, both you and your colleagues who are sitting before you, all of you are a symbol that I am about to introduce my servant, the Branch. As for the stone I have set before Joshua—on the one stone there are seven eyes. I am about to engrave an inscription on it,’ says the Lord who rules over all, ‘to the effect that I will remove the iniquity of this land in a single day. In that day,’ says the Lord who rules over all, ‘everyone will invite his friend to fellowship under his vine and under his fig tree.’ ” (Zechariah 3:8–10 NET)

Then say to him, ‘The Lord who rules over all says, “Look—here is the man whose name is Branch, who will sprout up from his place and build the temple of the Lord. Indeed, he will build the temple of the Lord, and he will be clothed in splendor, sitting as king on his throne. Moreover, there will be a priest with him on his throne and they will see eye to eye on everything. (Zechariah 6:12–13 NET)

The word “branch” or “shoot” is also used in prophecies to refer to the future glory of the Israelites (Isa. 60:21) and, more commonly, to the divinely appointed ruler. In Isaiah 11:1–5, the future son of David will be imbued with the divine spirit of wisdom, power, and God’s will in order to judge humankind in righteousness. God will establish a “righteous branch” of David out of Jesse’s stump whose way will be just (in contradistinction to that of Jeremiah’s contemporary, Zedekiah; Jeremiah 23:5; 33:15; cf. Ps. 132:17). His days will be characterized by security (Jeremiah. 23:5,6; 33:15,16), and the Israelites will always be ruled by descendants of David (Jeremiah 33:17–26). (19) Zechariah has prophecies about “my servant the Branch” (Zechariah 3:8 RSV) and “the man whose name is the Branch” (Zechariah 6:12 RSV). In these messianic prophecies, the image of the branch becomes a title for God’s coming leader, who will be both king and priest. Yeshua (Jesus) the Messiah (Christ) is the Branch! (14)

Who would have believed what we just heard? When was the Lord’s power revealed through him? He sprouted up like a twig before God, like a root out of parched soil; he had no stately form or majesty that might catch our attention, no special appearance that we should want to follow him. He was despised and rejected by people, one who experienced pain and was acquainted with illness; people hid their faces from him; he was despised, and we considered him insignificant. But he lifted up our illnesses, he carried our pain; even though we thought he was being punished, attacked by God, and afflicted for something he had done. He was wounded because of our rebellious deeds, crushed because of our sins; he endured punishment that made us well; because of his wounds we have been healed. All of us had wandered off like sheep; each of us had strayed off on his own path, but the Lord caused the sin of all of us to attack him. He was treated harshly and afflicted, but he did not even open his mouth. Like a lamb led to the slaughtering block, like a sheep silent before her shearers, he did not even open his mouth. He was led away after an unjust trial— but who even cared? Indeed, he was cut off from the land of the living; because of the rebellion of his own people he was wounded. They intended to bury him with criminals, but he ended up in a rich man’s tomb, because he had committed no violent deeds, nor had he spoken deceitfully. Though the Lord desired to crush him and make him ill, once restitution is made, he will see descendants and enjoy long life, and the Lord’s purpose will be accomplished through him. Having suffered, he will reflect on his work, he will be satisfied when he understands what he has done. “My servant will acquit many, for he carried their sins. So I will assign him a portion with the multitudes, he will divide the spoils of victory with the powerful, because he willingly submitted to death and was numbered with the rebels, when he lifted up the sin of many and intervened on behalf of the rebels.” (Isaiah 53:1–12 NET)

The Wooden Cross

In the ancient world, the word cross was often synonymous with crucifixion. It sometimes only consisted of an upright stake, but usually, a cross-beam was attached either on the top or in the middle of the stake. Crucifixion as a form of execution probably originated with the Persians. It was later appropriated by Alexander the Great, adopted by the Romans, and finally abolished by Constantine. It should be noted that the reference to the condemned person hanging on a tree in Deuteronomy 21:22–23 is not a reference to execution but is a public display of God’s curse subsequent to stoning. (26)

In the first century a.d. crucifixion was one of the strongest forms of deterrence against insurrection or political agitation in Roman provinces. Crucifixion was preceded by scourging. When the victim was affixed to the cross, he was stripped and mocked. The pain was extreme. After the victim died, the body was often left on the cross to decay and become food for scavengers. (26)

The imagery of the cross in the Synoptic Gospels expresses radical discipleship that leads to suffering and sometimes to martyrdom. Jesus demands that his followers be willing to deny themselves and “take up the cross” (Matthew 16:24; Mark 8:34). Luke’s version (Luke 9:23) emphasizes a daily commitment to this task. The expression “take up the cross” recalls the common practice of the condemned person carrying the cross beam to the place of execution. Such a demand entails that all who follow Jesus must be prepared to suffer and be crucified. Jesus’ road to suffering and eventual death by means of the cross (1) became an example of obedience and commitment to God for all who would become disciples. In this respect, the call to discipleship is a call to both self-denial and suffering. In John, the notion of being “lifted up,” which is understood as being part of the glorification process, is associated with Jesus’ crucifixion (John 3:14;12:32–34). Here the cross signifies victory. (26)

And although the New Covenant does not overtly underscore the image of a carpenter’s son dying on a wooden cross, it does present us with the image of Christ dying on a xylon, a word that can mean either “tree” or “wood” (Acts 5:30; Galatians 3:13; 1 Peter 2:24). Christian tradition has rightly perceived and elaborated the image of “the wood” as a cruciform symbol of redemption but also of judgment. (3)

The image of the cross in Paul is theological in import. Paul’s interest is in the saving significance of the cross as atonement and not in the historical reconstruction of the event. Paul interpreted Jesus’ agonizing and humiliating experience on the cross as an expression of obedience (Philippians 2:8), which accomplished the required redemption. Paul’s preaching of the cross, namely the crucifixion of the Messiah, does not correspond to established ideas of salvation in the Greco-Roman and Jewish religions (1 Corinthians 1:17–18). Rather it is seen as divine wisdom. Not only does the cross become associated with the death of Jesus, but more importantly it becomes inseparably bound to all components of Christian salvation (1). For Paul, the cross is the revelation of God’s power and wisdom. It dramatically signifies an all-encompassing reconciliation: it bridges the gap between humanity and God (Colossians 2:14); it breaks the barrier between Jew and Gentile (Ephesians 2:16), and it restores the entire cosmos (Colossians 1:20). Similar emphases on the effects of the cross are also described in Hebrews 12:2 and 1 Peter 2:24. (26)

Biblical Typologies, Metaphors, & Similes Series:

- The Old Leaven of the Kingdom of Darkness

- The New Leaven of the Kingdom of Heaven

- Wine

- Water

- Finely Sifted (Wheat) Flour

- Frankincense

- Myrrh

- Anointing Oil

- Olive Oil

- Honey

- Salt

- Waving and Heaving

- Barley

- Gold

- Silver

- Bronze

- Stone

- Wood

- Linen

- Iron

- Shofar and Trumpet

Shalom

(Security, Wholeness, Success)

Peace

Then he said to them, “Therefore every expert in the law who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like the owner of a house who brings out of his treasure what is new and old.” (Matthew 13:52 NET)

(1) Select the link to open another article with additional information in a new tab.

(2) Patricia L. Crawford, “Wood,” ed. Mark Allan Powell, The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary (Revised and Updated) (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), 1109.

(3) Leland Ryken et al., Dictionary of Biblical Imagery (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 962–965.

(4) Megan Bishop Moore, “Wood,” ed. David Noel Freedman, Allen C. Myers, and Astrid B. Beck, Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, 2000), 1386.

(5) Allen C. Myers, The Eerdmans Bible Dictionary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1987), 1064.

(6) “Wood,” Compton’s Encyclopedia (Chicago, IL: Compton’s Encyclopedia, 2015).

(7) Brand, C., Draper, C., England, A., Bond, S., Clendenen, E. R., & Butler, T. C. (Eds.). (2003). Cedar. In Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary (p. 274). Nashville, TN: Holman Bible Publishers.

(8) Masterman, E. W. G. (1915). Hyssop. In J. Orr, J. L. Nuelsen, E. Y. Mullins, & M. O. Evans (Eds.), The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia (Vol. 1–5, p. 1445). Chicago: The Howard-Severance Company.

(9) Moody, D. L. (1875). Life Words from Gospel Addresses of D. L. Moody. (G. F. G. Royle, Ed.) (p. 6). London: John Snow & Co.

(10) Not Used

(11) Kaiser, W. C., Jr. (1990). Exodus. In F. E. Gaebelein (Ed.), The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers (Vol. 2, p. 376). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

(12) Balfour, J. H. (1885). The Plants of the Bible (pp. 45–46). London; Edinburgh; New York: T. Nelson and Sons.

(13) Jeremiah Unterman and Mark Allan Powell, “Branch,” ed. Mark Allan Powell, The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary (Revised and Updated) (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), 104–105.

(14) Leland Ryken et al., Dictionary of Biblical Imagery (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 116–117.

(15) John D. Barry et al., eds., “Acacia,” The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

(16) John D. Barry et al., eds., “Cedar,” The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

(17) Mark Allan Powell, ed., “Cypress,” The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary (Revised and Updated) (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), 166.

(18) John D. Barry et al., eds., “Olive Tree,” The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

(19) Mark Allan Powell, ed., “Almug,” The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary (Revised and Updated) (New York: HarperCollins, 2011), 22–23.

(20) John D. Barry et al., eds., “Algum,” The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

(21) J. A. Motyer, “Burning Bush,” ed. D. R. W. Wood et al., New Bible Dictionary (Leicester, England; Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1996), 152.

Bibliography. U. Cassuto, A Commentary on the Book of Exodus, 1967; B. S. Childs, Exodus, 1974.

(22) Moisés Silva, The Essential Bible Dictionary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), 46.

(23) Walter A. Elwell and Barry J. Beitzel, “Burning Bush,” Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1988), 389.

(24) Leland Ryken et al., Dictionary of Biblical Imagery (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 130.

(25) John D. Barry et al., eds., “Burning Bush,” The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

(26) Leland Ryken et al., Dictionary of Biblical Imagery (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 184.